Abstract: In 1935 a book was published in Germany with essays by John Dewey, the most famous American philosopher, and his equally internationally-renowned pupil, William H. Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick’s essay, “The Project Method”, published in 1918 (September), had triggered a storm of enthusiasm in the USA to convert the curriculum of public schools to the project method, which, however, in principle, had been used decades earlier in manual training schools. The article is the starting point of a larger investigation which shows how Kilpatrick’s Project Method came to Germany when its popularity had already evaporated and criticism dominated. This attempt at historical construction is based on previously unpublished letters by Kilpatrick 1931-34. To do this, we must describe the contemporary background, in particular the relations between American and German specialists in education, which were institutionally fostered by the Teachers College of Columbia University, New York City, and the Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht (Central Institute for Education and Teaching), in Berlin. Both institutions were engaged in an exchange of educational experience through study trips until 1932. The different attitude and the ambivalence of Kilpatrick and Dewey with regard to the race question in the USA will also be mentioned. Claims of the more recent German Dewey reception that there was no interest in Dewey, Kilpatrick and American education in Germany between 1918-1932 are given critical examination.

Keywords: William H. Kilpatrick, John Dewey, Project Method, American-German relations in education; Peter Petersen

概要(Hein Retter:威廉· 克伯屈(William H. Kilpatrick) 方案教学法百年纪念:第一次世界大战后,德美关系背景下的进步式教育之里程碑): 1935年,在德国出版了由美国最著名的哲学家约翰· 杜威(John Dewey)和同样享有国际声誉的他的学生威廉· 克伯屈(William H. Kilpatrick) 共同撰写的一本书。克伯屈的文章 “方案教学法” 于1918年(9月)出版并引发了一股热潮。通过将公立学校中的教学计划转变为方案教学法,在原则上,已在几十年前的人工培训中有所运用。本文展现了克伯屈的方案教学法是如何来到德国,以及当它的受欢迎程度已经逐渐减退,批评占据主导地位。我们关于这一历史性结构的尝试是基于1931年至1934年克伯屈未发表的一些信件。因此,对当时的背景进行一下描述是必要的,特别是从属于纽约哥伦比亚大学师范学院和柏林中央教育学院的美国和德国的教育者们之间的关系。一直到1932年,两所机构共同努力,通过访学的方式来促进教学经验的交流。克伯屈和杜威对美国种族问题的不同态度及矛盾心理也有所提及。关于在1918年至1932年德国对杜威、克伯屈以及美国教育学没有兴趣的论断加以了纠正。

关键词:威廉· 克伯屈(William H. Kilpatrick),约翰· 杜威(John Dewey),方案教学法,德美教育关系, 彼得彼得森(Peter Petersen)

Zusammenfassung (Hein Retter: Das hundertjährige Jubiläum von William H. Kilpatricks Projekmethode: Ein Meilenstein in der Progressive Education vor dem Hintergrund der deutsch-amerikanischen Beziehungen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg): 1935 erschien in Deutschland ein Buch mit Essays von John Dewey, dem berühmtesten Philosophen Amerikas, und seinem ebenso international bekannten Schüler William H. Kilpatrick. Kilpatricks Aufsatz “The Project Method”, veröffentlicht 1918 (September), hatte in den USA einen Begeisterungssturm ausgelöst, den Lehrplan der öffentlichen Schulen auf die Projektmethode umzustellen, die jedoch im Prinzip schon Jahrzehnte zuvor in der manuellen Ausbildung verwendet worden war. Der Artikel bildet den Ausgangspunkt einer größeren Studie, die zeigt, wie Kilpatricks Projektmethode nach Deutschland kam, als ihre Popularität bereits schwand und die Kritik dominierte. Unser Versuch einer historischen Konstruktion basiert auf bisher unveröffentlichten Briefen von Kilpatrick 1931-34. Es ist notwendig, den zeitgenössischen Hintergrund zu beschreiben, insbesondere die Beziehungen zwischen amerikanischen und deutschen Pädagogen, die vom Teachers College der Columbia University, New York City, und dem Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht in Berlin institutionell gepflegt wurden. Beide Institutionen sorgten in Zusammenarbeit für einen pädagogischen Erfahrungsaustausch durch Studienreisen bis 1932. Erwähnt werden auch die unterschiedliche Einstellung und die Ambivalenz von Kilpatrick und Dewey in Bezug auf die Rassenfrage in den USA. Behauptungen der jüngeren deutschen Dewey-Rezeption, dass es in Deutschland 1918-1932 kein Interesse an Dewey, Kilpatrick und der amerikanischen Pädagogik gab, werden korrigiert.

Schlüsselwörter: William H. Kilpatrick, John Dewey, Projektmethode, Amerikanisch-deutsche pädagogische Beziehungen; Peter Petersen

Аннотация (Хейн Реттер: К столетию разработки У. Х. Килпатриком метода проектов: основополагающий концепт прогрессивной педагогики в контексте германо-американских отношений после Первой Мировой Войны): В 1935 году в Германии вышла книга очерков Джона Дьюи, известнейшего американского философа, и его всемирно известного ученика и последователя Уильяма Х. Килпатрика. Работа Килпатрика «Метод проектов», опубликованная в сентябре 1918 года, была с восторгом принята в США; все буквально ринулись перестраивать учебный план публичных школ, внедряя метод проектов, хотя его уже доводилось использовать несколькими десятилетиями ранее в обучении рабочим профессиям. В статье рассказывается о том, как метод проектов, разработанный Килпатриком, пробивал себе дорогу в Германии, в то время, когда его популярность практически сошла на нет и в научных дискуссиях по данному вопросу преобладали критические оценки. Предпринимаемая нами попытка исторической реконструкции данного этапа основывается на неопубликованных письмах Килпатрика в период с 1931 по 1934 гг. Для этого необходимо описать условия этого периода, в частности, контакты между американскими и немецкими педагогами, которые обеспечивались на официальном уровне со стороны Педагогического колледжа Колумбийского университета города Нью-Йорка и Центральным институтом воспитания и обучения в Берлине. Сотрудничая, оба этих образовательных учреждения до 1932 года осуществляли педагогический обмен опытом – направляли своих специалистов – соответственно в Нью-Йорк или Берлин – в ознакомительные поездки. В статье также затрагивается аспект, связанный с различием во взглядах Килпатрика и Дьюи на расовый вопрос в США. Корректируется оценка высказываемых в последнее время идей, что в Германии в период с 1918 по 1932 гг. не было интереса ни к трудам Дьюи, ни к работам Килпатрика, ни ко всей американской педагогике.

Ключевые слова: Уильям Х. Килпатрик, Джон Дьюи, метод проектов, американо-германские педагогические контакты, Петер Петерсен.

1. Introduction

William Heard Kilpatrick (1871-1965) was a well-known professor in the Philosophy of Education Department at the Teachers College of Columbia University (TCCU), New York City. In the first half of the 20th century TCCU became the leading institution of teacher training in the US, also the leading US institution of so-called “progressive” education, often connected with a liberal-left political attitude. The academic teacher who was considered the spearhead of that progressive direction within the wide field of education, was embodied by Kilpatrick. It was special circumstances that made Kilpatrick the leading figure in American project pedagogy for the next two decades. The aroused fire of American public-school teachers’ enthusiasm for the “project method” as the centre of a new curricular movement soon seemed to be extinguished in the face of the American nation’s economic and political challenges in the 1930s.

Although the expectations of supporters of the project idea were greater than could be confirmed by the reality of everyday school life, today we may say that the international long-term effects have been greater than one might have expected. Thus, it is quite normal for schools today, at least in Germany, to offer project days or even a project week as a supplement to the normal curriculum every school year. Children then choose a topic from a range of subjects and work on it in a group. The results will be presented to parents and the public at a closing event. Also, in other fields of learning, such as in management courses, in the arts or – as mentioned before – in vocational training “projects” play a role. Project-based learning today is one of the established alternative methods in school and the education system.

In September 1918, Kilpatrick published the short essay “The Project Method” which “catapulted [him] to fame” (Parker, 1992, p. 2). But Kilpatrick’s thoughts did not come out of the blue. The educational idea of the project had already gained a foothold in the United States more than three decades earlier, most strongly in manual training schools and vocational schools for the agricultural and industrial professions. Here project work developed in several didactic directions. A few years before the publication of his well-known 1918 essay Kilpatrick had already been involved in a “project” in TCCU teacher training. From 1916, the project method had been considered as a standard method in vocational schools and also mentioned in textbooks of general pedagogy in the USA (Knoll 2011, 272f). So, it was by no means new virgin territory that Kilpatrick entered with his essay. Rather, it was already a pedagogically cultivated area.

Such and more information with a detailed historical retrospect on the project idea, how it came from the USA to Europe and spread here during the economic and scientific success of an up-and-coming America, can be found in the book by Michael Knoll (2011). Knoll had also published his research in many individual articles in American specialist magazines since the 1990s. Today Knoll’s book, written in German, is indispensable if you want to orientate yourself in the history of the project concept. Knoll’s basic work of 2011 is in its last section particularly interesting for German readers, because in a concluding chapter the discussion of the project idea in the Federal Republic of Germany after the Second World War is documented. An important question for the German discussion of the project idea concerns John Dewey’s share in American project pedagogy and his particular influence on Kilpatrick’s project idea. Knoll addresses this question in detail, and I will return to this briefly in this essay. Earlier presentations of this subject (Magnor, 1976, III; Oelkers, 2009, p. 188f) require considerable revision.

This article outlines Kilpatrick’s project pedagogy based on his programmatic essay of 1918. Finally, it should be clear how Kilpatrick’s project plan came to Germany. There was a volume edited in 1935 by the German educationalist and representative of New Education, Peter Petersen (1884-1952). The book was entitled: “Der Projekt-Plan. Grundlegung und Praxis” (Petersen, 1935). It contained essays, translated into German, by both William H. Kilpatrick and John Dewey. For the first time in Germany texts by Dewey and Kilpatrick were placed under a common educational point of reference.

The first part of my research deals with the personal relationships of the actors and the time contexts from which this book emerged. As a source, which has not yet been sufficiently evaluated by educational history research, the journal “Pädagogisches Zentralblatt” (abbr. PZ) is used, published since 1921 by the “Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht” (abbr. ZEU; Central Institute for Education and Teaching), in Berlin. The legal status of the ZEU was a foundation, with a remit for all of Germany, but assigned to the Prussian Ministry of Education. In the last 30 years, Dewey’s leading interpreters in Central Europe have argued that the tradition of the monarchist German Empire had continued after 1918 in the mind of German educationalists, viz. in the Weimar Republic, Germany – in comparison to other countries – had been isolated from American democracy and the USA. And Dewey’s democratic ideas on education (inclusive of his “pragmatism”) had neither been known nor wanted at all – or “misunderstood”, at least watered down (Füssl 2004, p. 80f.) I would like to suggest a reassessment of this point of view. To be the saviour of the Germans was not Dewey’s intention.

Dewey’s contributions to Petersen’s edition of 1935, to begin with, are not a direct support of Kilpatrick’s concern to give recognition to the project idea but are texts that provided German readers with an insight into Dewey’s educational thinking before and after the First World War. Apart from Helen Parkhurst’s Dalton Plan, Kilpatrick’s project method turned out to be the most important conception of exported American Progressive Education after World War I (Holt, 1994). But we also know that the German translation of Kilpatrick’s and Dewey’s texts was published under Nazi rule. The contexts of the acting persons under the conditions of the Third Reich – not to forget Petersen’s change to Nazism in his publications – are to be dealt with in a following essay.

Today the textbooks of educational historians in German-speaking European countries (Germany, Austria, partly Switzerland) see the reception of Kilpatrick’s project idea as beginning with this book in 1935, containing treatises by Kilpatrick and Dewey. No one asked about the (hi)story that made this volume possible. That’s what my contribution will deal with. In view of racial bias that has still not disappeared in the USA, it is inevitable to touch on a problem that the American and German reception of the project method has so far pushed aside: the problem of the “color line” (W.E.B. Du Bois). We should ask, if the project method played a role in Kilpatrick’s and in Dewey’s thinking – perhaps – to see “projects” also as a tool of integration for white and non-white children in the class-room. This idea was realized, later, for example, with the Jigsaw Technique initiated by social psychologist Elliot Aronson (see his Wikipedia entry).

2. William H. Kilpatrick – Biographical Aspects and Academic Influences

Kilpatrick was a Southerner (in detail: Beineke 1998, pp. 1-50). Unlike John Dewey, whose hometown was Burlington, Vermont, he came from Georgia (GA). Born in White Plains (GA), the young William was socialized in a religious home; his father was a Baptist Church preacher. Kilpatrick took his B.A. at the small (Baptist) Mercer University in Macon (GA) in 1891, and one year later (after studies at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) his M.A. He first worked as a teacher and Principal at Georgia public schools from 1892-1897. “He returned to Mercer University as a professor of mathematics (1897-1906) and served as acting president (1903-1905). He went to Teachers College, Columbia University” (Bronars Jr. 1978, p. 746). Kilpatrick left Mercer University in a situation of conflict: “The trustees were concerned about his doubting the virgin birth” (Parker, 1992, p. 3). But the conflict was much deeper because Kilpatrick saw his integrity violated by personal accusations (Beineke, 1998, pp. 40-47).

During his time as a teacher Kilpatrick had already attended summer courses and spent shorter stays at several universities, so again in 1895 at Johns Hopkins. As early as 1893 Kilpatrick had visited Francis W. Parker, the “father of the progressive educational movement” (Dewey, LW 5, p. 320).i He was inspired by Parker’s “Quincy method” of free student learning, whereas, in summer 1898 at Chicago University, he did not find Dewey particularly impressive. In 1907 Kilpatrick enrolled at TCCU in New York City. Here Dewey (who had changed from Chicago to New York), Thorndike and Monroe were among his main teachers. With work on an historical topic he received his doctorate in 1912 from Paul Monroe at Columbia University. Kilpatrick spent the rest of his academic life there. At TCCU he became a lecturer in education in 1909, assistant professor in 1911, associate professor in 1915 and full professor in 1918, retiring in 1937 as emeritus professor. Kilpatrick remained associated with the TCCU throughout his life. He held many public offices in the service of the common good and received many academic honours (Parker, 1992, p. 4).

On the occasion of Dewey’s 100th birthday Kilpatrick wrote a short essay in 1959 (reprinted in 1966) about his encounter with him as a student at TCCU:

I entered upon my 1907 work with Prof. Dewey thinking that in philosophy he was still a neo-Hegelian. For a time, Dewey – along with many others – had followed his neo-Hegelian line; and I, too, after working in philosophy at Johns Hopkins in 1895-1896, had accepted it as my personal outlook. But now I found that Dewey, stressing the conception of process, the continuity of nature, and the method of inductive science, had built an entirely new philosophy, later called Experimentalism. As I worked with him during three constructive years, I gave up neo-Hegelianism and accepted instead the new viewpoint, thereby gaining a fresh and invigorating outlook in life and thought. From that time until Prof. Dewey’s death in 1952, I had great satisfaction in the many contacts with him. Dewey read and approved the manuscript of my 1912 book “The Montessori System Examined” (Kilpatrick, 1966, pp. 14-15).

Indeed, Kilpatrick always advocated John Dewey’s ideas. He was considered as the chief interpreter of Dewey’s pedagogy by many of his contemporaries and followers, regardless of whether his colleagues – or even Dewey himself, as some critics believe – thought this was appropriate or not. Also, personally, his close relationship with Dewey is evident. When a bust of Dewey was unveiled at a ceremony on November 28th, 1928, Kilpatrick “gave the main address extolling Dewey’s contributions to philosophy and education” (Dykhuizen, 1973, p. 235). Kilpatrick chaired the academic celebrations of Dewey’s 70th birthday in 1929 (ibid., p. 243). Kilpatrick was the editor of the volume “Educational Frontier” (1933), the basic book in which well-known academics from TCCU and other universities demanded “social reconstruction” under the spiritual leadership of Dewey. The book was an intellectual answer to America’s dwindling confidence in democracy in the face of people’s economic misery during the Great Depression but showed no interest in mentioning the race problems in American democracy (McCarthy & Murrow, 2013).

Kilpatrick was a founding member of the John Dewey Society in 1935, and editor of its first yearbook (Beineke, 1998, p. 218). On November 10th, 1947, in the distinguished presence of John Dewey, in a solemn meeting at TCCU, the William Heard Kilpatrick Award (the Kilpatrick Medal) was given to Prof. Boyd Bode and presented by Kilpatrick (ibid., p. 316). In 1951, Samuel Tenenbaum, Kilpatrick’s biographer, was successful in convincing Dewey to write an introduction to the book on Kilpatrick, after Dewey had benevolently taken note of Tenenbaum’s script – but also after emeritus Kilpatrick advised the young author to first delete certain names that might have caused Dewey displeasure (Beineke, ibid., p. 341).

By the way, in Dewey’s giant work this is his only essay on Kilpatrick’s project method – a special honor for Kilpatrick, forgetting earlier troubles with the often misunderstood “project”. If one checks the “Correspondence of John Dewey” (Dewey, 2005), the letters to Kilpatrick are throughout friendly; they show no hidden disagreement with Kilpatrick. In my view, at least three basic aspects of Dewey’s world of thought can be found in Kilpatrick: first, the commitment to a renewal (reconstruction) of education on the “progressive” path (for long, until now, a point of controversial debates in the Dewey reception), second, an experimental-pragmatic philosophy and, third, the commitment to democracy in the Deweyan spirit.

Apart from Dewey, the influence on Kilpatrick exerted by the famous psychologist at TCCU, Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949), can also be clearly felt. The philosopher Dewey and the experimental psychologist Thorndike were more opponents than friends in their different epistemological views (Tomlinson, 1997). It was Thorndike, not Dewey, who had the greatest success in professionalizing teacher training, by introducing empirical methods and research into learning theory (Retter, 2012, p. 295). Thorndike’s influence on Kilpatrick with his modern methods of empirical psychology and publishing successful textbooks must not be underestimated. Kilpatrick’s cognitive power to present complicated facts simply and catchily was more due to Thorndike’s than Dewey’s influence. Dewey was much more decisive for Kilpatrick’s philosophical messages on democracy and education. Kilpatrick was always talking about democracy in a thoroughly convinced and serious way, whereas with Dewey the democratic thought rather formed the foundation on which he built his political philosophy; the word “democracy” often remained in the background, as shown in particular in Dewey’s best-known book, “Democracy and Education” (1916, MW 9). Kilpatrick, as he later revealed, had a significant role in the creation of the book – we may call it Dewey’s ‘bible of democracy’:

When he [John Dewey] himself had finished seven chapters of “Democracy and Education” he turned these over to me for criticism and to suggest other topics for completing the book. I was then teaching a course in Principles of Education; so, I made a list of philosophic problems that troubled me in this course and turned them over to Dewey. At first, he rejected my list, but later he redefined a number of the problems and these now appear as chapters in the completed book (Kilpatrick, 1966, p. 15).

3. The Essay, “The Project Method” (W.H. Kilpatrick), 1918

Kilpatrick’s famous article on “The Project Method” which was in his time often reprinted and is now celebrating its 100th anniversary, begins with the following words (we quote a reprint from 1929, 11th edition):

The word ‘project’ is perhaps the latest arrival to knock for admittance at the door of educational terminology. Shall we admit the stranger? Not wisely unless two preliminary questions have first been answered in the affirmative: First, is there behind the proposed term and waiting even now to be christened a valid notion or concept which promises to render appreciable service in educational thinking? Second, if we grant the foregoing, does the word ‘project’ fitly designate the waiting concept? Because the question as to the concept and its worth is so much more significant than any matter of mere names, this discussion will deal almost exclusively with the first of the two inquiries (Kilpatrick, 1929, p. 4).

Kilpatrick points out that another term, such as “purposeful act”, could be suitable as a term for the presented pedagogical concept – and furthermore, the reader should not take the term “christened”, which he used, too seriously, for, as an educational term, “project” had been in use for a long time. Kilpatrick admits that he doesn’t know who the inventor is and warns his readers right at the beginning: “Not a few readers will be disappointed that after all so little new is presented.” (Kilpatrick, ibid.)

What is a project, pedagogically speaking? It is a “wholehearted purposeful act carried on amid social surroundings” (Kilpatrick, ibid., p. 5). We should note that Kilpatrick’s 1918 paper does not contain the subtitle he added to later reprints: “The Use of the Purposeful Act in the Educative Process”. The demand is not made here that the project method should take the place of the normal curriculum completely. In fact, in the years that followed, the general discussion went exactly in this direction.

Kilpatrick tells the reader in 1918 that he has long recognized the need to make the manifold relationships of the variables of educational processes practicable through a unifying concept. This term he looked for had to take into account in particular: “the factor of action, preferably wholehearted vigorous activity”, “the laws of learning”, “the ethical quality of conduct.” Kilpatrick is convinced that “education is life – so easy to say and so hard to delimit” (ibid., p. 3f.). It is important to see that Kilpatrick stresses the ethical dimension of purposeful action. We know, he has the reputation – not without reason – that his ideas on the project method tend to be child-orientated, emphasizing the child’s intentions in place of the requirements of the teacher on the basis of the normal curriculum. But one should not forget that the purposeful act, the project, that draws from the full steam of life, is integrated into a value system, ethical behavior and conduct, in a manner Dewey had described shortly before in “Democracy and Education”.

Nevertheless, the assignment of the project method to the so-called child-centered approach derives its right from the equation of “life” and “education”. Kilpatrick states that not all purposes of life are worthy, but the “project method” refers to the “purposeful act” as “the typical unit of the worthy life”. (We can add that, in particular, the child’s life is worthy, and “activity” is part of children’s life.) Vice versa “the worthy life consists of purposeful activity and not mere drifting” (Kilpatrick, ibid., p. 4).

You can see the change of view between “old” and “new” education in the light of the project method. The old thesis that education is preparation for life (the traditional interpretation) is replaced by the “progressive” thesis: that education “is life itself”. This is, however, originally not Kilpatrick’s idea, this view comes from Dewey. In “Democracy and Education”, published in 1916, Dewey said in chapter 18 (“Educational Values”):

Since education is not a means to living but is identical with the operation of living a life which is fruitful and inherently significant, the only ultimate value which can be set up is just the process of living itself (Dewey, MW 9, p. 248).

For today’s readers, it is important to know that this view is not realist populism but shows the radical nature of a philosophy that abolishes the difference between action and thought, practice and theory, fact and claim – in order to replace those differences by the biological unity of active ACTION. The old psychology (or better: physiology) divided action in stimulus and response, Dewey criticized. He replaced this difference by the claim that stimulus and response (which creates action) are only two phases of the same thing. Coordination happens between different parts of the same matter in an organic circuit. The conscious becoming part of the physio-psychic basis of action is called EXPERIENCE. Dewey assumed that action has its condition by instrumentally successful working coordination. The whole model, however, is a mixture of common sense and speculation – anyhow, it is not clear in the details. Strictly experimental psychologists of Dewey’s time, like Thorndike at TCCU or Charles Judd in Chicago (Dewey’s successor as professor there) could only warn against such thinking.ii

For the first time in 1896, Dewey developed the elements of his new logic of instrumental experimentalism in his essay “The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology” (EW 5, pp. 96-109). Of course, Dewey’s holistic concept, transferred to psychology and pedagogy, can also open up new insights. So, the subject ‟pedagogy and pragmatism” was indeed new and fascinating twenty years ago. On the other hand, one should also critically analyze the consequences if, at the same time, – for whatever reason – universal recognition of Dewey’s pragmatic view was demanded by some Deweyans. Neither the special features of Dewey’s concept were taken into account, nor were the pragmatic enthusiasts of pedagogical pragmatism aware that Dewey did not identify his own notion of action with “pragmatism”, even though he was one of the founding fathers of “American Philosophy”. So, it was not astonishing that some contemporary educationalists tried to prove that German pedagogy, blinded by nationalism, couldn’t recognized the value of Dewey’s pragmatism and his thinking on democracy (Böhm & Oelkers, 1995; Tröhler & Oelkers, 2005; critically Retter 2009, p. 191; 2015; 2016). Indeed, the core of Dewey’s view of “pragmatism” is neither to be found in Peirce nor in James. Louis Menand stressed that Dewey’s organic circuit “is biologized Hegel” (Menand, 2001, p. 329). Kilpatrick, however, was far from plumbing such depths in Dewey’s philosophy. He saw the whole thing in a more practical way. Kilpatrick formulated, standing in the bucket line with Dewey (without mentioning Dewey):

A man who habitually so regulates his life with reference to worthy social aims meets at once the demands for practical efficiency and of moral responsibility. Such a one presents the ideal of democratic citizenship. […] As the purposeful act is thus the typical unit of the worthy life in a democratic society, so also should it be made the typical unit of school procedure. We of America [sic!] have for years increasingly desired that education be considered as life itself and not as a mere preparation for later living. The conception before us promises a definite step towards the attainment of this end. If the purposeful act be in reality the typical unit of the worthy life, then it follows that to base education on purposeful acts is exactly to identify the process of education with worthy living itself. The two then become the same. (Kilpatrick, ibid., p. 6).

We can conclude that the normative basis of Kilpatrick’s project method is the idea that the equivalence of education with life is only conceivable regarding the claim of conduct, of valuable ethical action as part of the “good life”. This idea then finds its acme insofar that the thus normatively determined educational process has a democratic quality. The democratic citizen in a democratic society is both a prerequisite and an objective of the project method. The project method as the foundation of the educational process seems to eliminate all motivational problems of the students, from Kilpatrick’s point of view: ‟There is no necessary conflict in kind between the social demands and the child’s interests” (ibid., p. 12), because those disorders of children’s interest are (or should have) now have been eliminated that the traditional school had generated.

It is striking that Kilpatrick hardly talks about the teacher’s role in the project method. Indirectly, it becomes clear that the teacher does not play a bossy, dominant role, but is rather the preparing arranger of open-start situations in the role of a coordinator. There is also no question here of checking what has been learned. The teacher has to steer the child through the difficulties which accompany project work. Tasks can be too simple or too difficult, the use of required tools must first be learned etc. Anyway, Kilpatrick stated: “The teacher’s success – if we believe in democracy – will consist in gradually eliminating himself or herself from the success of the procedure” (ibid., p. 13).

Today one should add: This is an old educational wisdom, but in a modern performance society absolutely far from reality. At least in the normal learning process, the theoretical demands of the teaching contents grow with the increasing age of the pupils in higher education. At the end of this introduction to Kilpatrick’s project method, let’s hear him speak again when he distinguishes four different types of projects:

Let us consider the classification of the typical kind of projects:

Type 1, where the purpose is to embody some idea or plan in external form, as building a boat, writing a letter, presenting a play;

Type 2, where the purpose is to enjoy some (aesthetic) experience, like listening to a story, hearing a symphony, appreciating a picture;

Type 3, where the purpose is to straighten out some intellectual difficulty, to solve some problem[s], e.g. finding out whether or not dew falls, to ascertain how New York outgrew Philadelphia;

Type 4, where the purpose is to obtain some item or degree of skill or knowledge, like learning to write at grade 14 on the Thorndike Scale, or learning the irregular verbs in French.

It is at once evident that these groupings more or less overlap and that one type may be used as a means to another end. It may be of interest to note that with these definitions the project method logically includes the problem method as a special case” (Kilpatrick, ibid., p. 16)

Kilpatrick defines the so-called problem-based method as a special case of the project to eliminate it as a competing model and explains these four types. He considers that the Type 1 projects (sometimes also Type 4) have an inner structure which he sees as a loose sequence of “purposing, planning, executing and judging”. We know these elements are Herbartian pedagogical tradition, as Dewey made use of it in “How we think” and in his late work, “Logic. Theory of Inquiry”, in a five-step scheme. The general idea of Kilpatrick’s paper is repeated at the end: to establish the “wholehearted purposeful activity in a social situation as the typical unit of school procedure”. This conception should be “the best guarantee of the utilization of the child’s native capacities now too frequently wasted”. Kilpatrick closed:

With the child naturally social and with the skillful teacher to stimulate and guide his purposing, we can especially expect that kind of learning we call character building. The necessary reconstruction consequent upon these considerations offers a most alluring ‘project’ to the teacher who but dares to propose (Kilpatrick, ibid., p. 18).

Last century, at the beginning of the twenties, there was great enthusiasm for Kilpatrick’s project method in US public schools and other educational institutions. This meant the end of the traditional school subjects. They were to be replaced by life-orientated projects in which groups of children acquire the skills and knowledge they would otherwise learn in specialized traning. Knoll (2011) shows in detail the rise and fall of Kilpatrick’s project pedagogy in the USA. One of the main points of criticism was that thorough knowledge was not sufficiently acquired in the projects but was rather a condition for projects with higher expectations. The structure of the subjects cannot be dispensed with. Also, according to Kilpatrick, the children determine their actions themselves to a large extent and the role of the teacher is not sufficiently defined. The term “project” is unclear and replaces clarity with “flexibility”. In the end, Kilpatrick no longer wanted to use the term ‘project’; he preferred to speak of a ‟wholehearted, purposeful activity” which needs an ‟activity program” (Tenenbaum 1952, pp. 248); privately, in a letter, he admitted to having made a mistake (Knoll, ibid., p. 132). Historically we should see this not as a defeat, but as a readiness to learn.

German educators were well informed about the then current US discussion on progressive education and the project movement. They evaluated the discussion in American journals. In a report about the ‟project method” the PZ informed German teachers (written in German):

No wonder, then, when we hear that the method suffers no less from some of its followers than from its opponents and that many teachers and school inspectors are suspicious of it; and many adults who cannot get rid of their own school tradition probably want to dismiss it with the expression “soft pedagogy”. Nevertheless, the method is used successfully in most newly established schools and in many existing state schools. (Unfortunately, nothing precise can be determined about the number). As a result, it is emphasized that the children of schools with “project teaching” have sufficient knowledge in the elementary subjects but are mentally much more advanced than the pupils in other schools. […] Behind it stands the whole modern educational science of the United States, represented in the narrower sense here by W.H. Kilpatrick (“The Project Method”; Teacher Coll. Col. Un.), in the following by J. Dewey. The “Project Method” is therefore a concrete attempt to put the educational principles given there into practice (Friebel, 1927, p. 34).

In no way was this report of a German education specialist with US experience an attack on the American project method, but smiling, friendly and hopeful. In a report informing German readers about new teaching methods in the USA, the mathematics methods expert D.W. Reave, TCCU, said:

The project method has been used considerably, especially in the lower grades. It has not found favour, however, in the secondary schools; and its use in elementary schools is condemned by some authorities (Reave, in Lietzmann, 1931, p. 260).

4. Thomas Alexander and the USA-Germany Exchange of Experience in Education

Until the First World War, institutional relations between scientists in the USA and the German Empire were diverse and friendly. Many American scientists had studied and received their doctorates at German universities. For the young academic subject of psychology, Wilhelm Wundt (1833-1920) had an international reputation at the University of Leipzig. (Petersen was an academic pupil of Wundt; he became his first biographer in 1925). Regarding education, Wilhelm Rein (1847-1929), a professor at Jena University, was an international magnet, also for Americans. Similarly, philosophy at the universities of Berlin, Heidelberg and Freiburg attracted Americans. William James (1842-1910), who had studied in Germany, was highly regarded by his German colleagues, in particular by Carl Stumpf and Friedrich Paulsen, at Berlin University. The First World War subsequently thoroughly destroyed German-American relations. In 1923, the Weimar Republic was still a state where it was not clear whether it would survive the constant crises in the face of imminent political upheavals within and imminent military intervention from without. The Rapallo Treaty with the Soviet Union in 1925 and the acceptance into the League of Nations (to which the USA did not belong) in 1926 strengthened the Weimar Republic.

Before the First World War, American students of philosophy, psychology and education came to Germany in large numbers to study there. In the twenties the opposite tendency becomes apparent: after the First World War, the German Reich had become a democratic republic (Weimar Republic). Now German educators wanted to find out more about progressive education in the USA. In the Weimar Republic there were many new reformist pedagogical directions, which, however, were also interesting for educational reformers in the USA. Among those interested in Germany was Prof. Thomas Alexander, TCCU, who published his positive impressions of the new educational developments in Germany (Alexander & Parker, 1929). Alexander (1931) informed German educators about the state of development of experimental schools at American universities and teacher training institutions, including the TCCU, not without self-criticism.

Dr. Georg Kerschensteiner (1854-1932), former director of state schools in Munich from 1895-1919, was honorary professor at the University of Munich from 1920. He is regarded as the nestor of the German vocational school and the idea of the work school in the public education system, which he realized in the elementary schools of Munich. In the years before World War I he travelled to the USA, where he became familiar with the conditions school and education. Since then he was friends with John Dewey. In 1925 Kerschensteiner compared the educational system in Germany with that of the USA in an essay in the PZ. He did not deny a certain backwardness of public education in America and the lower standards at American universities – not least by citing self-critical voices from the USA. On the other hand, he stressed the rapid progress made by the US education system. Kerschensteiner recommended German government agencies to learn from the Americans, and he recommended a constant exchange of experience between German and American educators (Kerschensteiner, 1925, p. 13).

It was a good coincidence that a German official of the Prussian Ministry of Education, Erich Hylla (1887-1976), travelled to the USA and to the TCCU on behalf of his minister to find out about American education, teacher training and curricula. Hylla had grown up in Silesia. After an educational career, he also studied psychology at the University of Breslau (Wrocław) – under William Stern, with a focus on diagnostics. He became school superintendent of Eberswalde (near Berlin); in 1922 he moved to the Prussian Ministry of Education. One of his tasks here was the development of curricula in the school system and it was for this reason that he was in the USA in 1926/27 to gather new experience there.

In fact, there was a need on the German side to learn from America and its pedagogy. In 1926, Hylla made the first contacts relevant to the American journey of German educationalists. He got to know both Dewey and the professors at TCCU. As Bittner (2001, 88, Fn. 5) writes, the invitation of a group of German educators to the TCCU was envisaged with Prof. del Manzo. R.T. Alexander was at the ZEU in Germany in 1926 and discussed such a project with Franz Hilker, the educationalist and foreign department manager at ZEU (Böhme, 1971). Günther Böhme, who documented the history of the ZEU between the two World Wars, emphasized the importance of Alexander for the international recognition of the ZEU by strengthening German-American relations. Böhme wrote (transl. H.R.):iii

Especially lasting and strong were the relationships that were able to be established with the American school system […]. They have become momentous not only through the growing recognition of the ZEU as Germany’s pedagogical centre, but also for Hilker’s development towards comparative pedagogy, for which Thomas Alexander in particular opened his eyes. He first visited the ZEU in 1926 in the course of his studies on German pedagogy. Together with Hilker, he prepared the program for the visit of a group of the “International Institute of Teachers College of Columbia University”, to which Thomas Alexander belonged. The study trip was conducted by Thomas Alexander in 1927 and was reciprocated by a pedagogical study trip to the United States of about 30 [actually 25; H.R.] German educators under Hilker’s direction in 1928. During his stay in the United States Hilker held lectures at the Teachers College of Columbia University […] Until 1933 student and study groups came to Germany every year under Alexander’s leadership (Böhme, 1971, pp. 149-150).

It is uncertain if such a study trip of American education specialists to Germany actually took place in 1927, as Böhme asserted (ibid., 150), because the PZ did not report any such event. It could be that the plan was limited to visiting the 4th World Conference of the New Education Fellowship (NEF), which took place in Locarno (Switzerland), in August 1927.

Who was Alexander? [Richard] Thomas Alexander (1887-1971), born in Smicksburg, Pennsylvania, had studied as a teacher in the USA and, under John Dewey’s influence, was committed to progressive pedagogy. Even before the First World War he had been interested in reform pedagogy in Europe. First, he was in Turkey, then in Germany. In 1908/1909 Alexander had studied under Wilhelm Rein in Jena. Until the war started he traveled more than once to Germany to study school and education. He worked from 1914 to 1924 at George Peabody College in Nashville (Tennessee), and in 1917 he earned a PhD degree with a historical study of the Prussian school system, a work that is still hard to surpass and set standards (Alexander, 1919). In 1924, he joined the TCCU, New York City. Alexander became Deputy Director of the ‘International Institute’ at the TCCU, founded in 1923.

The Director of the International Institute was Kilpatrick’s doctoral supervisor, Prof. Paul Monroe. Apart from his long-time academic friend William F. Russell, Alexander’s colleagues in Education at the TCCU were (among others): William H. Kilpatrick, Isaac L. Kandel, Robert B. Raup, Georg S. Counts, Harold Rugg and William C. Bagley. Alexander was the initiator of the foundation of the “New College”, which from 1932 introduced a new concept of teacher training as an independent unit of Teachers College, but it had to close in 1939.

John Dewey, who taught philosophy at Columbia University, was associated with the TCCU through a lectureship. The TCCU professors were mostly Dewey’s followers, but not all of them – and not all of them with the same enthusiasm as Kilpatrick.

In the “International Institute” of the TCCU Alexander was regarded as the Germany expert – not without good reason, although Kandel, who had emigrated from Europe to the USA, also possessed a broad and excellent knowledge of education in Europe. Kandel had also spent a guest semester with Wilhelm Rein in Jena before the First World War, in 1907. In the twenties Alexander also contacted Rein’s successor in Jena, Peter Petersen – and was impressed. He was an intern at the University school in Jena, which had the status of an experimental school. It is the place of origin of the so-called Jena Plan (usually written in German as “Jenaplan”).

In his 1929 book Alexander described a day trip for the children of the Jena University School and accompanied a group of Petersen’s students on a pedagogical excursion with the aim of meeting the socialist school reformers in Vienna (Alexander & Parker 1929, pp. 58-63; pp. 63-66). In the “Mitteilungen” (news and reports) from the Petersen Institute in Jena, the “Whitsun trip to Vienna” in the summer semester of 1926 is listed along with many other study trips (Petersen, 1929, p. 13). Petersen had been Professor of Educational Science at the University of Jena since 1923. He repeatedly emphasized Alexander’s positive role for Jenaplan pedagogy:

Inspired by the visits of Prof. Alexander of Columbia University and his colleagues, we wish that the “minimum subject matter” for spelling, geography and history could also be worked out for the German circumstances (Petersen, 1932, pp. 71-72).

In the chronicle of the “Erziehungswissenschaftliche Anstalt” (Petersen’s Institute in Jena) the lecture of “Prof. Marie Steinhaus-Moskau” is mentioned, “which at the same time in July 1927 showed a valuable part of the exhibition of the ‘Russian Working School'”, organized by the ZEU, in Berlin. Furthermore, lectures by “Miss Lucille Allard and Prof. Dr. Thomas Alexander -Newyork” and by “Prof. Dr. Raup – Newyork” are documented (Petersen, 1929, p. 14; Retter, 2007, p. 162).

After the First World War it was Alexander at the International Institute, TCCU, who successfully sought to re-establish contacts between American and German educators. He was friends with the German reform pedagogues, in particular with Fritz Karsen, Franz Hilker and Peter Petersen (see Wikipedia entry: Richard Thomas Alexander). Karsen, the socialist school reformer from Berlin, accepted Alexander’s invitation in 1926 to get to know the pedagogy of the USA for six months (Karsen 1993, p. 10f.). Hilker and Petersen did this in 1928 as members of a delegation of 25 school principals and experts in school administration from all over Germany. After agreement between Alexander and Hilker, the TCCU had invited and organized the program for the contact trip.

5. Concerning education: Contemporary historical aspects of German-American relations

There is a wealth of research on the German-American cultural exchange in the context of study visits and contacts between American and German academics before and after 1900, which is not considered here (see also Füssl, 2004). Daniela Bartholome (2012) examined the network of the Berlin university philosopher Friedrich Paulsen (1846-1908) with his friends at American colleges and universities. In the era of the German Empire, studying in Germany was much more popular than studying in France and England for American students (Bartholome, ibid., p. 133). The idea of the German university had influenced the development of higher education in the USA. In the USA, however, the educational qualification required to enter university before the First World War was usually lower than the German ‘Abitur’ (Bartolome, ibid., p. 133).

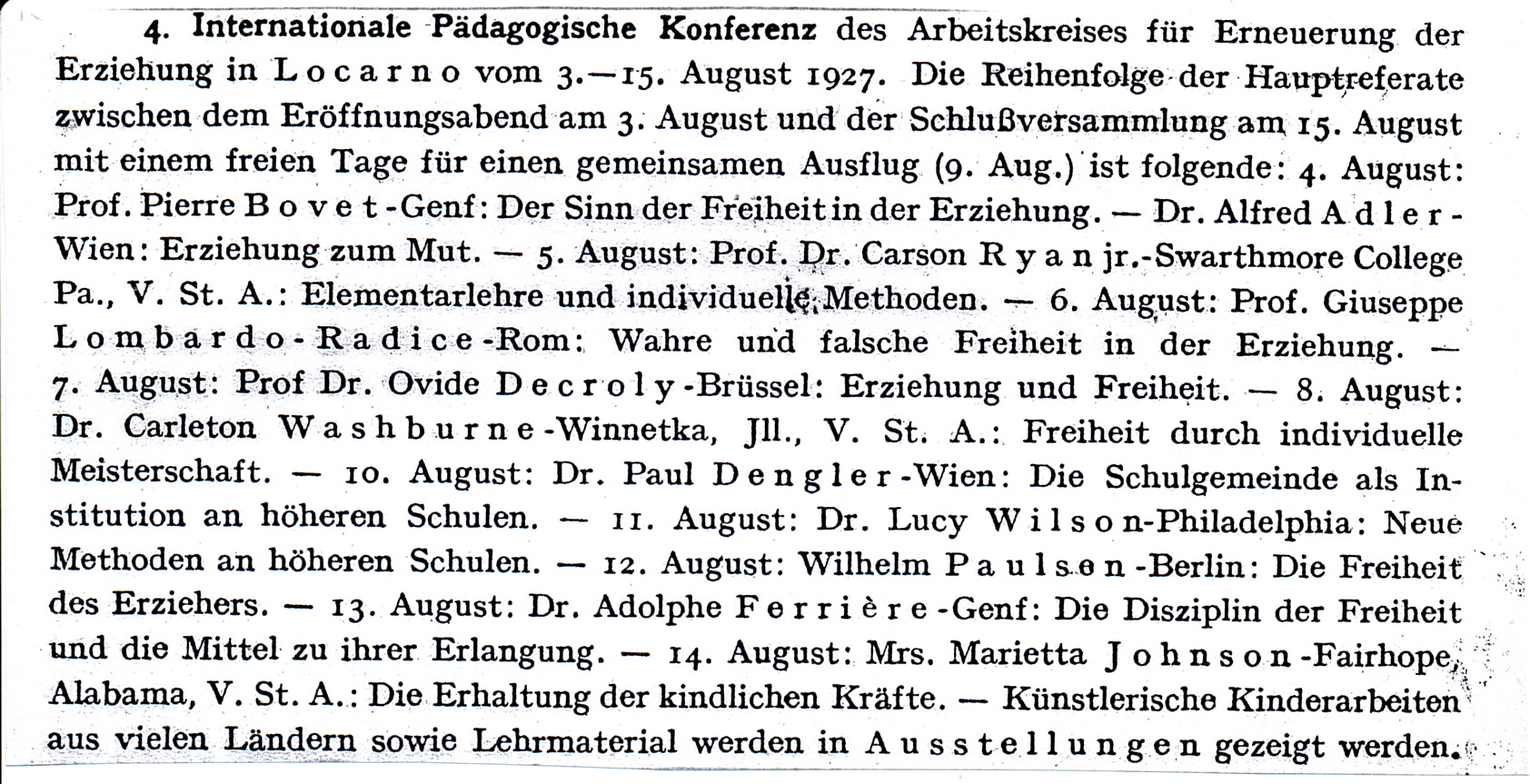

The official visit of German educators to the USA on an institutional level in 1928 was preceded three quarters of a year earlier by contacts between American educators and colleagues from German-speaking countries and regions. A large number of educators from the USA – to be exact 162 (Koslowski, 2012, p. 64) – travelled to the 4th World Conference of the New Education Fellowship (NEF) in Locarno in August 1927. From several sources (Kluge, 1992; Retter, 2007, p. 171f.; Koslowski, 2012, p. 64) it can be reconstructed that Petersen saw T. Alexander again in Locarno, and he got to know Harold Rugg (TCCU), as well as C. Washburne (Winnetka) and Marietta Johnson (Fairhope). He met them all for a second time the following year in the USA, with the German travel group; the “Winnetka Calculation Method” was developed by Washburne, which made charting individual learning progress possible. Petersen was to introduce this at the time at his Jena University School (Petersen, 1930, p. 199). The PZ published the main lectures of the Locarno Conference from 3rd to 15th August 1927 in advance:

Main lectures at the 4th NEF World Conference, Locarno, 1927. Source: Pädagogisches Zentralblatt, 6, 1927, p. 452

The German group’s trip to America in the spring of 1928, which included the educationalists Friedrich Schneider (Bonn/Cologne) and F.E. Otto Schulze (Königsberg) in addition to Petersen (Jena), was led by Franz Hilker. He headed the foreign department of the ZEU in Berlin, a pedagogical centre in the Weimar Republic whose importance for the dissemination of new pedagogical developments internationally and in Germany through teacher training, courses and public relations work in the Weimar Republic can hardly be underestimated (in detail, Tenorth, 1996). As Deputy Head of the ZEU, Hilker was also editor of the PZ, the monthly magazine of the ZEU.

The PZ published essays by leading experts from educational science and practice and informed about all new pedagogical developments including school legislation, advanced training courses, pedagogical conferences – in Germany and internationally. There was a close connection between the ZEU, which had two branch offices in Köln and Essen, and the ministries of education of the German states (Länder), so that important events such as the educational exchange between the USA and Germany via the official gazettes of the Länder ministries of education, which began in 1928, reached German pedagogues nationwide (Füssl, 2004, p. 72f.). But already in the years before, the PZ had occasionally published essays and book reviews about the education system in the USA.

Reports by Franz Hilker (1928) and Friedrich Schneider (1970, 18-23), but also Petersen’s letters, which he wrote to his wife in Jena, prove how important the trip to the United States was for the German participants in 1928. Relevant parts of Petersen’s reports in his letters were published by Barbara Kluge (1992, pp. 202-223) Petersen was fascinated by the experiences he gained from this journey and stay in the USA. By far the most important person of the American-German welcome evening on April 4th, 1928, in New York, was without doubt John Dewey. Hilker reported:

[Then] John Dewey, the revered old leader of American education, also spoke to us in his simple, winning manner (Hilker, 1928, p. 529).

Petersen’s first impression of Dewey was very similar – namely filled with great respect, as the letters to his wife show; the same applies to the “old Kilpatrick” he had now met. Kilpatrick was 13 years older than Petersen, who was 25 years younger than Dewey. Petersen had mentioned Dewey and his famous Laboratory School in Chicago in his 1926 book “The New European Educational Movement” which lasted until Dewey’s departure from Chicago in 1904. Petersen told his wife, Else, about the American-German welcoming evening in a letter:

First, old John Dewey spoke, wisely philosophically from the silent world of ideas. What is all this for me, Else, I know this name, I’ve been using it for 20 years, now I’m standing in front of him, shaking hands, talking to him and knowing that in autumn, if he’s still alive, I’ll discuss with him… On Wednesday he’ll talk to Kilpatrick, to us, I’ll see K. [Kilpatrick] as well. Thorndike also spoke to us. I know his work, I need it a lot – as you know… Now I’m sitting right in front of this man…” (Petersen, in Kluge, 1992, p. 204).

Edward L. Thorndike, whom Petersen also met for the first time, was no stranger to Petersen from 1922 at the latest, after Thorndike’s “Psychology of Education” had become known in German in 1922 (translated by Otto Bobertag, a pupil of William Stern). An academic highlight was the participation of the German group in the conference of American university teachers at the TCCU on general problems of education in the USA. Hilker reported to his German readers in the PZ:

At the opening ceremony, the member of our study society Prof. Dr. Peter Petersen -Jena spoke as the first speaker of the day about Germany’s relations to American pedagogy (Hilker, 1928, p. 530).

Petersen wrote to his wife in Jena:

Yesterday, April 4th, was a serious day for me; they had me as – first speaker on the program of the 1st National Americ. Conference of Education – I had after the first words my full rest; spoke slowly, clearly, with warmth etc. and had a full success. Dr. Alexander said “very well delivered” and it depends on his judgment (Petersen, in Kluge, ibid., p. 204).

The German group completed a round trip of many weeks through a large number of schools and educational training centers in the USA. Friedrich Schneider and Peter Petersen had an invitation from Peabody College in Nashville to hold summer school courses, arranged by Alexander. At the Demonstration School at George Peabody College (established by Alexander during his time at Peabody College) Petersen introduced elements of the Jena Plan. He wrote later:

From April to October 1928 I was invited to the USA to visit various cities (New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Columbus (Ohio) , Detroit, Ann Arbor, Winnetka, Milwaukee, Chicago, Iowa (JA), Raleigh (NC), Boston) and to give lectures during the summer semester 1928 as guest professor at the George Peabody College in Nashville (Tennessee), as well as to set up an experimental class according to the so-called Jena Plan (Petersen, in Kluge, ibid, p. 199).

As Hilker mentioned the Germans stayed in New York until April 11th, 1928; a series of lectures at the TCCU had been organized for them, and they attended the TCCU training schools in New York. Nicolas Murray Butler, President of Columbia University, had greeted the German guests at their first reception at the TCCU. Butler, 1931 Nobel Peace Prize winner, was a widely educated philosopher. After receiving his doctorate in 1884, he had studied in Berlin and Paris. For him, the American-German contact with professors was the resumption of a great tradition of Columbia University and the TCCU, which he himself had initiated decades ago. In 1887 Butler became president of the New York School for the Training of Teachers, which in 1893 was renamed Teachers College. Beginning as a school to prepare teachers for the children of the poor, the College affiliated with Columbia University in 1898 as the University’s Graduate School of Education, with a co-educational experimental and developmental unit (the Horace Mann School) – and flourished thereafter.

As President of Columbia University since 1901, Butler negotiated regular guest lectures with Kaiser Wilhelm II in Germany in 1905 through an exchange of professors between Columbia University in New York City and the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin. Butler’s signature can be found on the agreement (Paulus, 2010, p. 74). As a student at Berlin University, Butler had a friendly relationship with the German philosopher Friedrich Paulsen (1846-1908) until his death. This is shown by their correspondence which had existed since 1884.

The fact that Paulsen had a direct influence on Columbia is confirmed by a completely different source in the welcoming statement of the Associate Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, Robert H. Fife (Professor of German Language):

[Translation] Certainly Columbia must welcome a society of German educators with special joy, because it owes so much to German pedagogy. […] There is at least one German ideal of university life that Columbia includes in its creed. This is the necessary and indissoluble combination of teaching and research. This crowning characteristic of German universities, which Friedrich Paulsen once described with unforgettable eloquence, is in fact the working principle of all larger US universities […] (Fife, 1928, p. 534).

Under the influence of Paulsen’s university ideas, Butler contributed to the development of pedagogy in the USA into an independent science after 1900 through the further expansion of the Teachers College, New York (Bartholome, p. 120; p. 157f.). This was not least achieved by the appointment of John Dewey to Columbia University, although Dewey worked much more on philosophical than on educational topics in New York. Immediately before the USA entered the war, Butler fought against all “anti-American” (i.e. German-friendly or neutrality-oriented) tendencies at his university. After the end of the war he promoted the resumption of relations with the universities in the Weimar Republic. In 1926 Butler’s book, “Der Aufbau des amerikanischen Staates”, was published in German in Berlin. Alan Ryan stressed:

One reason why the Teachers College had been established in the first place was the experience of American liberals who had gone to Germany; they found German educationalists imaginative, open-minded, and kindly and German schools old-fashioned, rigid and brutal (Ryan, 1995, p. 163).

The Dewey biographer Ryan was right. The law and order rule in the educational system of Prussia, which was the mirror of a monarchic estate society until 1918, was mentioned also by Alexander (1919, preface). This was completely unimaginable for Americans but did not mean that there was nothing to learn for America’s schools, Alexander added. In the elementary schools, (but not everywhere in grammar school), this situation was overcome in the political system of the Weimar Republic. Here one could find a strong interest on the part of many teachers in ideas of New Education.

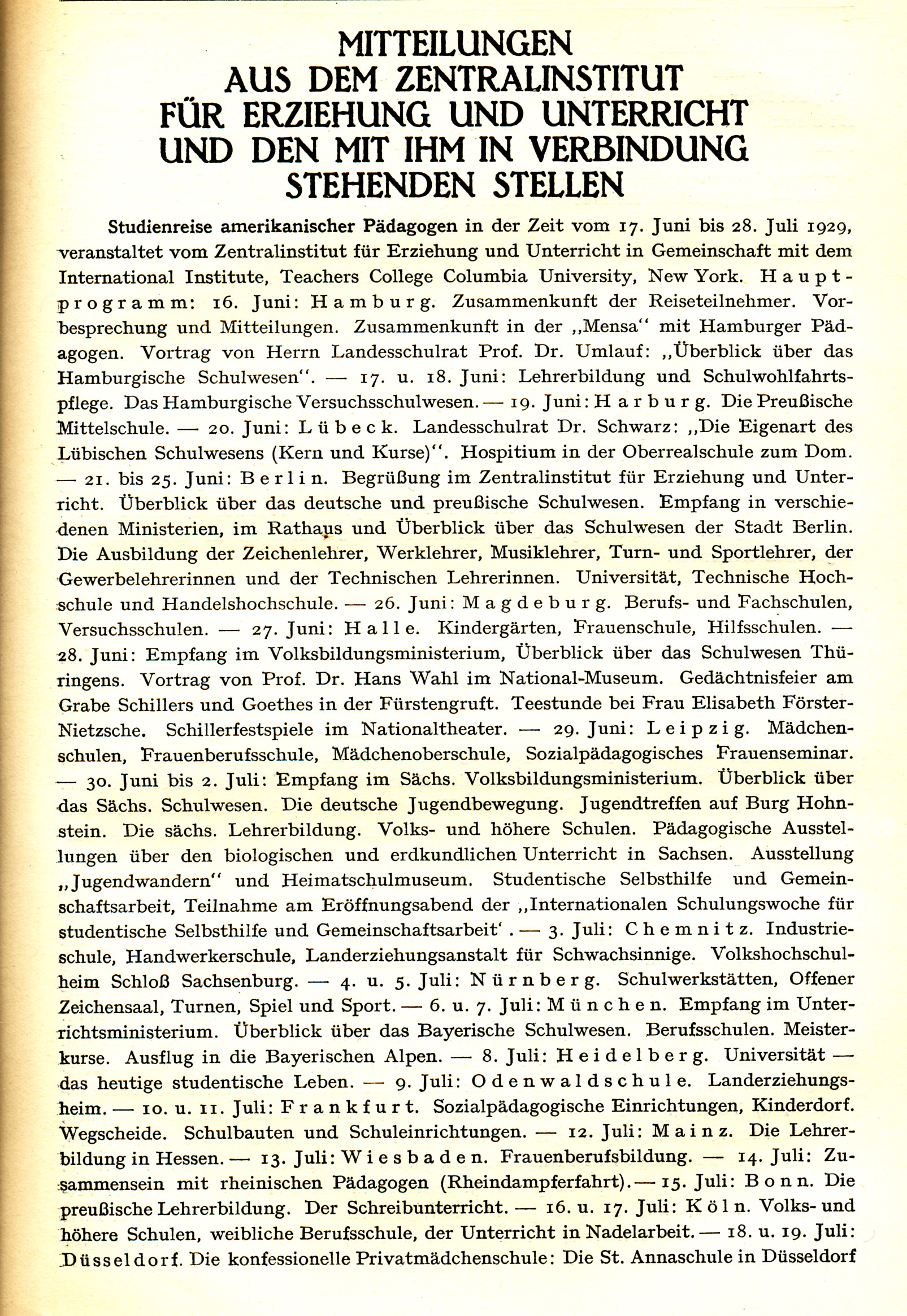

The detailed travel plan of the American pedagogues for their study stay in Germany from 17th June to 28th July 1929 appeared in the PZ (1929, p. 381f.) (see appendix). The programme included attendance in several school classes, participation in conferences and discussions at all administrative levels – from the simple school to school supervision up to the Ministries of the States (Länder) of the Republic, like Hesse, Saxony, Thuringia, Bavaria and Prussia. Excursions to cultural monuments, some with German colleagues, were part of the accompanying programme; the 1929 programme, for example, provided for a “get-together with Rhine pedagogues (a Rhine steamer cruise)”. The American travel groups were not isolated but integrated into the diversity of German educators in the individual provinces.

The University School in Jena is not mentioned as a place of visit. But the leader of the group of visitors who, as described above, went to the University school in Jena for a surprise visit on July 8th and 9th, 1929, “Miss Lefarth”, can be identified. It was the German-American Hedwig Lefarth, who was the contact person for Petersen at his stay in the USA in 1928, in particular during his guest professorship at George Peabody College, Nashville (Kluge, 1992, p. 217f.).

For the end of August 1929, the PZ had drawn attention to an offer of lectures by American lecturers, with the title: Lectures by professors at Columbia University New York (Teachers College) on education and educational science in the United States. The lecture series took place at the Pedagogical Institute Mainz under Prof. Erich Feldmann (PZ, 1929, p. 466). The success of this 6event is reflected in the number of 1,200 participants (Retter, 2007, p. 187). This meeting became the starting point for Kilpatrick’s correspondence with his German colleagues, first with Feldmann and later with Peter Petersen. Entries in Kilpatrick’s diary make clear that he was pleased to meet Petersen in 1928 and impressed by Petersen’s liberal views; on the other hand, Kilpatrick ‘s impressions from his German stay in Mainz, in August 1929, were very ambivalent.iv

One month earlier, from 17th – 28th July, 1929, the American study trip had taken place in Germany. At that time, in 1929, Petersen held a visiting professorship in Chile; he could neither welcome his American colleagues in Mainz, nor the study group from the USA that found out about the German education system in July 1929. Neither could Petersen attend the 5th NEF Conference in Helsingör, which took place from 8th – 21th August 1929 – with 240 (!) participants from the USA (Koslowski, ibid., p. 64). US specialists interested in the reform of education showed a great deal of interest in European reform concepts after the crisis of progressive education had become reality in their own country. This may have been one more reason why Petersen’s school surprisingly attracted attention in the USA even though he was not at all in Jena.

The teachers of the “Petersen-Schule” had to prepare weekly reports for each school year in which they documented the behavior of the children, the lessons and conspicuous events. For the 13th week of the school year 1929/30, 8th – 13th July 1929, Förtsch, the teacher who led the middle group, commented:

[Monday and Tuesday, 8th – 9th July, 1929]: Visit of 17 Americans, led by Miss Reid and Miss Lefarth and coming from the Odenwald School, who arrived here on Sunday afternoon. Since Prof. Johannsen [deputy director of Petersen’s University Institute] was unable to attend due to illness of his child, Dr. Döpp-Vorwald [assistant] and I had arranged their visit to the school and all related questions. On Monday of 7th-11th our guests were present in all groups of students. At 11 a.m. sharp the bus stood ready to take us […] in 1½ hours to the Landerziehungsheim Ettersberg [country boarding school, founded by Hermann Lietz]. It had been set up so that we could have lunch together. A guided tour through the home by Dr. Windweh and the visit of a small drawing exhibition by Mr. Beckmann lasted about 4 hours. So, we still had enough time to visit the Schiller House and the Goethe House in Weimar, and at the end we walked through the park. We were all highly satisfied with this day and returned to Jena in the most joyful mood around 8 o’clock. On Tuesday they again were present in our school […] (University Archive Jena. Stock S I, No. 151).

In PZ, 10, 1930 (p. 367) there is an announcement: “Second study trip of American education specialists to Germany”, with an indication of the program. The places named are Bremen, Hamburg, Dresden, Weimar, Stuttgart, Munich and Oberammergau, Frankfurt am Main, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Essen, Berlin, from 22nd June to 2nd August 1930.

The study trip of American educators to Germany in 1931 was announced as a joint event of ZEU and TCCU, with the note that the TCCU was certified as proof of qualification for participation in this “course on comparative education” (Studienreise 1931, p. 337). In the PZ the official announcement was as follows:

For 1932 there are no entries for study trips or a cooperation between TCCU and ZEU in the PZ. It is indicated that Prof. Alexander, TCCU, was taking over the management of a newly-founded academy which was to introduce a new form of teacher training (PZ 12, 1932, p. 43f.). This has been mentioned above, the academy was The New College.

6. John Dewey’s “Democracy and Education” – Aspects of the German Dewey Reception

From 1928 until the end of the Weimar Republic, good institutional contacts existed between the New York International Institute at the TCCU and the Berlin ZEU. Hilker’s travel report, titled “Pädagogische Amerikafahrt”, opened the October issue of PZ, 1928. This essay was followed in the same issue by contributions from American professors and the welcoming lectures given by the representatives of TCCU and Columbia University in German translation – and then also Kilpatrick’s lecture (“Philosophie der Erziehung”) and Kandel’s lecture (“Der amerikanische Geist der Erziehung”).

Not only Kilpatrick, but also some of his colleagues, whose contributions were published in 1928/1929 in the PZ, referred to the importance of John Dewey for New Education; this was especially the case with Prof. Robert B. Raup, who, as mentioned above, had already given a lecture in 1927 in Jena, together with Petersen. In several articles in the PZ, Bagley provided information about school and teacher training in the USA, and he was quite self-critical with regard to the qualification level of the lecturers.

Kandel’s address on the occasion of Dewey’s 70th birthday, 1929, about Dewey’s reception abroad, also mentioned Germany. He highlighted the long-known dissertation at the University of Halle by Lucinda Boggs (1901) and quoted Kerschensteiner’s esteem for Dewey in detail. Kandel mentioned that German students, if they did not speak English, had had little opportunity to get to know Dewey, and at the same time he emphasized Hylla’s recently published German translation of Dewey’s “Democracy and Education”. Kandel stressed:

The International conferences on education, especially that of the New Education Fellowship, are focusing marked attention on American education and the forces that made it and will inevitably lead to widespread study of its leading philosopher and interpreter. Similar results may be expected from the growing interest abroad in American life and thought and the exchange of educational visits (Kandel, 1930, p. 73f.).

Kandel was right with his thesis that until the appearance of the German translation of “Democracy and Education” in the Weimar Republic, Dewey was much more readily acknowledged by secondary literature than by translated original writings. As early as 1910 Aloys Fischer, the international, highly-esteemed Munich university Professor of Pedagogy, had expressed his opinion of John Dewey, who was not too well-known even in America at the time, in the leading German psychology journal, “Zeitschrift für pädagogische Psychologie” (Journal of Educational Psychology):

Recently, the German side has repeatedly referred to the educational work of John Dewey, and rightly so, in particular for his writings on “School and Society”, “the present situation of pedagogy”, “morality in education” and so on. Not only the American school problem is discussed in a fundamental way, but the problem of education, as it exists for modern democracy, for the constitutional state in general, is dealt with; more profoundly, more fruitfully, more incisively than by those who hope for salvation from all kinds of hygienic and methodological improvements and lose themselves in the otherwise useful special details of didactics (Fischer, 1910, p. 376).

Dewey’s pragmatic logic was by no means not completely unknown in Germany before the First World War. In the published Leipzig dissertation of the Canadian psychologist John MacEachran (1910), accepted by Wilhelm Wundt, interested people could find sufficient information (in German).

The war not only prevented contacts, it also changed attitudes. Dewey developed a particularly critical relationship towards the Germans. In “German Philosophy and Politics” (1915) he tried – not strikingly – to prove that Kant’s dualism, reinforced by Hegel’s absolutism and Nietzsche’s “will to power”, was the cause of German nationalism, which had led to the German war against the Entente in Europe in 1914. This was also an endorsement of the USA’s entry into the European war. Dewey was convinced that America should give a clear signal in fighting for democracy. Friends who were also his critics on this point, like Jane Addams, saw in this statement, as the socialist Max Eastman put it, more “a contribution to the war effort rather than to philosophy” (Eastman, in Ryan 1995, p. 191). People were shocked by the “brutality of the pragmatist position” as it was spelled out by Dewey, Ryan commented (ibid., p. 195).

There is something more to remember. At the beginning of the 21st century, Jürgen Oelkers (2000, p. 3f.) lamented the failure of Germany pedagogues to not, like Dewey, have combined education and democracy (Oelkers, 2000, p. 3f.), presenting Dewey’s “German Philosophy and Politics” as a new discovery. Oelkers followed Dewey’s logic without any historical distance and without seeing that Dewey’s treatise was one of many reactions that flared up in Europe, as well, after the outbreak of war, trying to injure the other side with national disgust.

Kerschensteiner in Germany, for instance, published a blazing call, “Offener Brief an meine amerikanischen Freunde” (Open letter to my American friends) that they should “not be misled by the lies of our enemies” (Kerschensteiner, 1914, p. 385). Oelkers’ context of discovery, presented with an accusation, was hardly suitable for becoming a resilient context of justification, because the moral accusation – unlike historical analysis – does not pose any reflexive critical questions and doesn’t tolerate any contradiction. Dewey had expressed in his “war script” of 1915 (MW 8, pp. 108-204), and in “Democracy and Education” (MW 9, 103; 105), that the Prussian ideal of the nation state demanded the subordination of the individual to the state, i.e. the anti-democratic equation of social with national education. A social idea binding democracy, as Dewey advocated it, was not viable for him in Germany – never. It would be negligent to present Dewey’s view a hundred years ago today as scientific truth without considering the context and showing the weakness of his reasoning.

It is quite correct to claim that in the German Empire Bismarck’s social laws were state policy against the Social Democrats. But this could prevent neither the strengthening of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) after 1890 nor the November Revolution of 1918. In the subsequent Weimar Republic the SPD-dominated Prussia led to a further expansion of social policy in favour of the workers, i.e. the foundation of the so-called welfare state in the German (Weimar) Republic. And Dewey? Unfortunately, his idea of “social” only had to do with good neighbourliness and the sharing of experience, and less with political decision-making. Thus, his social idea remained an idea – naturally valuable, proclaimed with an impressive power of persuasion that can almost be described as quasi-religious (Retter, 2018a). But even today, the world’s most powerful democracy, the United States, still lacks a network of social security for the underclass, especially for the poor, sick and elderly; we know that Western European standards are much higher. Why? Dewey, who constantly spoke of the change of society for the better, hated the European idea of the state and disdained the “machinery” of the big parties in his own country. What a pity! That the condition of the leading political parties is an important indicator of the quality of democracy, Dewey suppressed. Current views on Dewey’s social philosophy are primarily moral appeals to follow it without analyzing its problems.

In the years following the First World War, Dewey first spent time abroad to complete his important philosophical works before retiring. For him, the Germans were politically backward and not capable of democracy. R.T. Alexander’s effort at some differentiation was not visible here in Dewey’s statements. However, Dewey’s view of Germany, which was understandable from the point of view of state policy until 1918, contradicted the friendly contacts of all colleagues who, like George H. Mead, had studied in Germany. The lectures on pedagogical topics put up some defense against the growing dissatisfaction with the progressive education that fascinated America’s educators. In Turkey and China, where he was invited for a longer stay, “Democracy and Education” had been translated in 1928. In Japan, which understandably did not appeal to him politically, the complete translation only appeared long after the Second World War. Even in Mexico, where Dewey gave lectures before his trip to Europe in the summer of 1926 and reported on his impressions (LW 2, p. 194f.; p. 199f.; p. 206.f), a translation of his book did not promptly follow. Seen in this light, the appearance of the German translation of “Democracy and Education” in 1930 was by no means a requiem in the choir of European translations, but a forerunner for the dissemination of Dewey’s educational philosophy on the continent, an achievement that was also important for Austria and Switzerland.

Hylla published his German book about his US experience in 1928, entitled, “Die Schule der Demokratie” (The School of Democracy), meaning the comprehensive school system of public education (Hylla, 1928a). An essay on Dewey’s view of education followed (Hylla, 1929). Germany only had a comprehensive system in a few reform schools. Petersen’s repeated efforts to expand the Jena University School – it was an eight-year elementary school (Volksschule) – into a comprehensive school with 10 and 12 school years respectively, were foiled by the Ministry of Education in Thuringia. Also, in 1928, the German America scholar Georg Kartzke published a book about American schools, colleges and universities, but without mentioning Dewey. That was different with Hylla. In his book as well as in several essays in the PZ (Hylla, 1929), he stood up for John Dewey. In addition, Hylla’s America book also provides information about the Winnetka Plan (C. Washburne), the Dalton Plan (H. Parkhurst) and Kilpatrick’s project method. In the same journal he had previously published a treatise on educational research in the USA. (Hylla, 1928b). His essays were related to his book. Together with Kartzke’s book on the American school system, Hylla’s study was reviewed in detail by Hilker, in PZ 8, 1929, p. 482.

On behalf of the ZEU, Petersen published the book series “Pädagogik des Auslands”: monographs that either report on the pedagogy of a country or come from well-known reform specialists in education abroad. In some volumes, such as Adolphe Ferrierè’s book “Pädagogik der Tat”, John Dewey plays a major role, so that his name was present at several levels of reception in Germany. However, only the thin volume “The School and Society”, in the German translation of 1905, provided information in the Weimar Republic on Dewey’s practical pedagogy. But apart from the volume “Schools of To-Morrow”, dating from 1915 (which had some problematic racial aspects), Dewey had not written a book of pedagogical significance until then (This changed in the thirties).

The information on American pedagogy available to the broader pedagogical public in Germany from 1928 onwards was much more substantial than can be said for other countries, although essays and information on education in the Soviet Union can also be found several times in the PZ. Seen in this light, doubts are permitted about the assertion: “Especially with Hylla’s translation of Democracy and Education a new phase of understanding began” (Bittner, 2001, p. 84). When Dewey’s book appeared in German in 1930 (translated by Hylla), it received many reviews documented by Bittner (2001, p. 231) – also in the official magazine of the Prussian Ministry of Education and in all important teachers magazines. The German educators were well prepared for the appearance of Dewey’s “Democracy and Education. Most initial translations of “Democracy and Education” into European languages did not take place until after the Second World War. Search engines such as WorldCat now provide online access to national libraries, so the fact is verifiable.

In short, this is the result of my research: First, there was no ideologically or nationalistically based, particular obstruction of Dewey’s pedagogy in Germany. There was no German “national defensive struggle against Dewey”, as Bittner (2001, p. 67f.) claimed. But there were different attitudes and assessments, also critical voices; this is simply diversity of opinion. Compared to the fact that Dewey had many more opponents in his own country, that was perfectly normal. Secondly, even Dewey, who can be said to have always been guided by good intentions, has been confused in some political diagnoses, and on several occasions, he failed to translate his ideas into long-term successful practice (Retter, 2016).

7. Conclusion

Interpreters of the Dewey Renaissance in Switzerland and Germany after 1990 regretted that Dewey was unknown in Germany and that his pragmatism was hardly noticed (Oelkers, 1993; Bittner, 2000; 2001; Tröhler & Oelkers, 2005). But the sources evaluated here don’t confirm this impression. Furthermore, sources that have not yet been taken into account prove that Dewey’s nimbus found serious critics outside his following (see Retter, 2012; 2016; 2018b). The awakening resistance among colleagues at Teachers College, whose spokesmen were Bagley and then Kandel, primarily concerned progressive education. But Dewey was by no means out of the line of fire. The extenuating argument fell that Dewey had been misunderstood or that the moderately-judging Dewey has nothing to do with the radicals of progressive education. This criticism is discussed in another part of my research. The same basic criticism that King & Swartz utter from an African-American view today, has existed for a long time but has hardly been noticed:

During the early twentieth century, white progressive child-centered philosophers and educators like John Dewey, George Counts, and William Heard Kilpatrick advocated that schools become sites of democratic practice. However, their worldview and adherence to a racial hierarchy trumped their rhetoric and blocked them from acknowledging and learning from black scholars who were working at the same time – scholars such as W.E.B. DuBois, Carter G. Woodson, Anna Julia Cooper, Alain Locke, and Horace Mann Bond” (King & Swartz, 2018, p. 20).

A historical reassessment of Dewey and Kilpatrick is hard to circumvent, at least in some regards. In fact, it has already begun (Konrad & Knoll, 2018).

Abbreviations

- PZ

- Pädagogisches Zentralblatt (Pedagogical Central Magazine)

- SPD

- Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany)

- TCCU

- Teachers College, Columbia University, New York City

- ZEU

- Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht (Central Institute for Education and Teaching)

APPENDIX – Program of American Pedagogues in Germany, 1929.

Programme, July 17th-28th, 1929: Study visit of American education specialists to Germany

Source: Pädagogisches Zentralblatt, 9, 1929, p. 381

Programme, July 17th-28th, 1929: Study visit of American education specialists to Germany Source: Pädagogisches Zentralblatt, 9, 1929, p. 382

Endnotev

References