Abstract: With the reunification of Germany, a Jenaplan School was founded in 1991 in the city of Jena, Thuringia. Since then one place of the city carried Petersen’s name. The University School at Jena, refounded by Petersen as Life Community School in 1924 (the traditional purpose as a mere teacher training school goes back to the year 1844) and received international attention during the Weimar Republic. Petersen’s attempt to gain recognition in the Hitler state (1933-1945) with his reform pedagogy failed, but the University School was allowed to continue to exist. In 1950 it was closed by the socialist GDR state (East Germany). Ten years ago, a bitter dispute raged in Jena over Petersen because previously unknown racist texts written by him had been discovered. The dispute ended when Petersenplatz was renamed “Jenaplan”. A book by Hein Retter, which appeared ten years ago, was highly controversial: it described children of Jewish and socialist origin as well as disabled children – from families who were threatened by Nazi ideology but who saw their children safe with Petersen. Looking back ten years, the author of the controversial book describes the Jena Petersen dispute and what can be learned from it.

Keywords:reform pedagogy, Jenaplan, Jena University School, Petersen dispute, National Socialism, Holocaust

摘要 (Hein Retter: 一场关于改革派教育家彼得 · 彼得森(1884-1952) 2010年在耶拿发生的争论:十年后的”全面灾难”之回顾):随着德国统一,1991年在耶拿(图林根州)成立了耶拿普兰学校。自那时起,这座城市的一个广场被命名为彼得森。在耶拿的大学学校(自1844年以来,仅是一所面向师范生的实践学校)在1924年由彼得森新建为”社区学校”。在魏玛共和国时期,它得到了国际上的关注。彼得森在希特勒州(1933-1945)的改革教育中希望获得承认的尝试虽然失败了,但大学学校被允许继续存在。1950年,它被民主德国关闭。在发现彼得森的特别种族主义文本之后,十年前在耶拿爆发了一场激烈的争执。这场争执以将彼得森广场更名为”耶拿普兰”而告终。海因·瑞特十年前出版的一本书引起了极大争议:所描述的是犹太和社会主义背景的家庭,以及受到纳粹意识形态的威胁,却带着孩子的那些从属于大学的残疾儿童的家长们。回顾过去十年,这本有争议的书的作者描述了耶拿彼得森的争论,历史的进展以及可以从中学到的东西。

关键词: 改革教学法,耶拿普兰,大学学校,彼得森之争,国家社会主义,大屠杀。

摘要 (Hein Retter: 一場關於改革派教育家彼得· 彼得森(1884-1952) 2010年在耶拿發生的爭論:十年後的”全面災難”之回顧):隨著德國統一,1991年在耶拿(圖林根州)成立了耶拿普蘭學校。自那時起,這座城市的一個廣場被命名為彼得森。在耶拿的大學學校(自1844年以來,僅是一所面向師範生的實踐學校)在1924年由彼得森新建為”社區學校”。在魏瑪共和國時期,它得到了國際上的關注。彼得森在希特勒州(1933-1945)的改革教育中希望獲得承認的嘗試雖然失敗了,但大學學校被允許繼續存在。 1950年,它被民主德國關閉。在發現彼得森的特別種族主義文本之後,十年前在耶拿爆發了一場激烈的爭執。這場爭執以將彼得森廣場更名為”耶拿普蘭”而告終。海因·瑞特十年前出版的一本書引起了極大爭議:所描述的是猶太和社會主義背景的家庭,以及受到納粹意識形態的威脅,卻帶著孩子的那些從屬於大學的殘疾兒童的家長們。回顧過去十年,這本有爭議的書的作者描述了耶拿彼得森的爭論,歷史的進展以及可以從中學到的東西。

關鍵詞: 改革教學法,耶拿普蘭,大學學校,彼得森之爭,國家社會主義,大屠殺。

Zusammenfassung (Hein Retter: Der Streit um den Reformpädagogen Peter Petersen (1884-1952) in Jena 2010: Rückblick auf eine “totale disaster” nach zehn Jahren): Mit der Wiedervereinigung Deutschlands wurde 1991 in Jena (Thüringen) eine Jenaplanschule gegründet. Ein Platz der Stadt trug seitdem Petersens Namen. Die Universitätsschule in Jena (die als bloße Übungsschule für LehrerstudenInnenseit 1844 existierte) wurde von Petersen 1924 als “Lebensgemeinschaftsschule” neu gegründet. Sie fand in der Weimarer Republik international Beachtung. Petersens Versuch, auch im Hitlerstaat (1933-1945) mit seiner Reformpädagogik Anerkennung zu finden, schlug fehl, doch die Universitätsschule durfte weiter existieren. 1950 wurde sie vom DDR-Staat geschlossen. Vor zehn Jahren tobte in Jena ein erbitterter Streit, nachdem besonders rassistische Texte Petersens entdeckt worden waren. Der Streit endete mit der Umbenennung des Petersenplatzes in “Jenaplan”. Ein Buch von Hein Retter, das vor zehn Jahren erschien, war hoch umstritten: Geschildert wurden Familien jüdischer und sozialistischer Herkunft sowie Eltern behinderter Kinder, die von der Nazi-Ideologie bedroht wurden, doch mit ihren Kindern zur Universitätsschule gehörten. – Im Rückblick auf die zehn letzten Jahre schildert der Autor des umstrittenen Buches den Jenaer Petersen-Streit, den Fortgang der Geschichte und das, was man daraus lernen kann.

Schlüsselwörter: Reformpädagogik, Jenaplan, Universitätsschule, Petersen-Streit, Nationalsozialismus, Holocaust

Резюме (Хейн Реттер: Дискуссии о педагоге-реформаторе Петере Петерсене (1884-1952) в Йене в 2010 году: ретроспективный взгляд на «тотальную катастрофу» – десять лет спустя»):

После объединения Германии в городе Йене (федеральная земля Тюрингия) была открыта школа с системой организации «Йена-план». С того времени одна из площадей города носила имя Петерсена. Петерсен основал экспериментальную университетскую школу в Йене (до этого она, начиная с 1844 года, функционировала как учреждение подготовки студентов-педагогов) в 1924 году и трансформировал ее в воспитательную общину. В период Веймарской Республики педагогическая модель Петерсена получила международное признание. Попытка Петерсена обеспечить своей школе признание и в период нацистского правления (1933-1945) успехом не увенчалась, хотя университетская школа и продолжала существовать. В 1950 году политическое руководство ГДР закрыло школу. Десять лет назад в Йене разразились ожесточенные споры о наследии Петерсена, после того как были обнародованы труды Петерсена с расистским подтекстом. Закончилось все тем, что площадь, названная его именем, была переименована и стала называться «Йена-план». Книга Х. Реттера, увидевшая свет десять лет назад, тоже оказалась резонансной: в ней рассказывалось о семьях еврейского и «социалистического» происхождения, о семьях с детьми-инвалидами: все они преследовались режимом, но в тоже время продолжали принадлежать к общине. Автор нашумевшей книги вспоминает те годы, рассказывает об острых дискуссиях по поводу Петерсена и его концепции, описывает, как развивались события дальше и говорит об уроках, которые нужно извлечь из этой истории.

Ключевые слова: реформаторская педагогика, «Йена-план», университетская школа, дискуссии о наследии Петерсена, национал-социализм, Холокост).

1. The City of Jena in Thuringia 100 Years Ago

It seems to make sense to extend the review of the city of Jena in Thuringia, the place of the events of the following chapters, not to ten, but to one hundred years. One hundred years ago, on May 1, 2020, the Free State of Thuringia of the German Empire was founded from seven principalities – hardly viable on their own – after the fall of the German Empire. At the time, this meant the end of a geographically unprecedented disruption of the smallest territories, which had existed for several centuries with an abundance of exclaves in the middle of Germany. The newly created unity became possible after the German November Revolution in 1918 and the entry into force of the “Weimar Constitution” on 11 August 2019. Because of continuing political unrest in Berlin, the elected German National Assembly met in Weimar – until 1945 the capital of Thuringia – from 6 February 1919 to draw up a democratic constitution for the first German republic after the end of the monarchy.

In 1923, the government of Thuringia, which at the time was politically extremely left-wing, appointed Peter Petersen (1884-1952), a senior teacher from Hamburg, to the Chair of Education (Educational Science) at the State University of Jena (which received the name Friedrich Schiller University in 1934). The city of Jena was also the largest industrial location in Thuringia due to the Carl-Zeiss industrial enterprises (known worldwide for the manufacture of precision optical instruments) and the Schott glass works. Both companies were – since 1919 100% – part of the Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung (see Stutz, 2018). The children of both companies’ managers and workers formed the main contingent of the pupils who shaped the spirit of the reform school established by Petersen. Simply called the “Petersen School” in Jena, it was officially called the “University School” from 1926. From a formal point of view, it was an elementary school for grades 1-8 and, as an experimental school, belonged to the Educational Science Institute of the University of Jena, where Petersen worked. In this school, which had been founded with 20 pupils at Easter 1924, there was a large proportion of children from social democratic and communist families.

During the Weimar Republic, conservative and right-wing parties gained in importance during the 1920s. Thus, from 1930, Thuringia became the first territorial state in the German Empire in which Nazi ministers co-ruled the state, headed by Wilhelm Frick (NSDAP), under Erwin Baum (Thuringian Land Association) as the leading minister of state (Leimbach, 2018, p. 65f.). A number of bourgeois parties formed a coalition with the Nazis. The Social Democratic Party (SPD), with 32% of the voters’ votes being the actual winner of the elections, went into opposition. The Hitler Party (NSDAP) had achieved a share of 11% of the votes in the elections to the Landtag on December 8, 1929 (Dressel, 2010, p. 90). In view of the economic crisis, the NSDAP continued to gain support in Thuringia, as everywhere in Germany. From the end of August 1932, Thuringia was the state in the German Reich in which the incumbent Nazi government led by Fritz Sauckel, who later became Reich Governor, merged seamlessly into the Hitler state of 1933.

While in Weimar (the city of Goethe, Schiller and German Classicism) Hitler’s party, the NSDAP, achieved peak voter favour in the Reichstag elections of 1932/33, in Jena the NSDAP became the strongest party, but together the left-wing party spectrum was far superior to the Hitler party in purely numerical terms. It should be noted that since 1928, the KPD (the Communist Party) which was loyal to Moscow, led an ideological campaign of destruction against the SPD, the Social Democrats, which was also weakened by splitting off groups. A comparison of the results of the Reichstag elections on March 5, 1933 in the city districts of Jena and Weimar shows the considerable strength of left-wing parties in the industrial city of Jena compared to the capital Weimar under the (since January 30, 1933) incumbent German Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

| City districts | NSDAP | SPD | KPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jena | 33,4 | 25,9 | 18,3 |

| Weimar | 49,7 | 15,7 | 11,9 |

Figure 1: Results of the Reichstag elections of March 5,1933 for NSDAP, SPD and KPD; comparison of the city districts of Weimar and Jena; figures in percent (Dressel, 2010, p. 134f.).

2. Historical Aspects – the Transition from the Weimar Republic to National Socialism

Peter Petersen became known as the founder of the reform pedagogical school model “Jena Plan” (other spellings: Jena-Plan, Jenaplan) and from the second half of the twenties onwards his University School was widely recognized by pedagogues who were striving for a reform of the school system in the sense of “New Education”. Petersen’s reform idea was not modernist, but “new-conservative”: instead of the modern classroom principle (with students of the same age group), he returned to the mixed-age learning group, for which he introduced new principles of school life. This resulted in particular advantages for highly gifted children as well as for children with disabilities and developmental delays. A constant stream of domestic and foreign visitors who came to Jena led to the University School. For Petersen, New Education meant firstly the independent organisation of learning by the pupils, secondly a changed role of the teacher, thirdly a rich school life, with elective courses to promote creative and manual skills, also with the participation of parents.

In the Hitler state, Petersen succeeded in saving his school from closure, although all those interested in education in Jena knew that Petersen’s pedagogy had been born in the intellectual awakening of the Weimar Republic. In order to expand his pedagogy, called “Jenaplan”, Petersen’s pedagogy in Jena was strongly associated with Social Democratic reformers during the educational awakening of the Weimar Republic, but from the beginning it also had its own reform profile, which was fed by an idea that in the 19th century was a particular source of inspiration for the democratic renewal of the school system. This idea originates from the legal sphere of early Romanticism, as developed by the jurist Otto von Gierke (1841-1921) in social and cooperative law: Applied to the school, this means that the school is not to be understood as a compulsory institution of the state, but is ideally supported by a free association of parents (“Genossenschaft”). Parents are the main stakeholders in the education of their children: as a co-operative, they are keen to be jointly responsible for the education of their children in the best possible school, whereas the state has economic obligations (in the payment of teachers) and a more occasional supervisory function.

The Protestant pedagogue Friedrich Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1824-1893) realized this idea in the School Community movement. This first emerged in the Calvinish-reformed school system and has a tradition especially in the Netherlands, also in the US states. Parents have much more rights and duties of participation than in the traditional state school system. In Jena, the Petersen School remained attractive for all people, especially for the educationally conscious workforce, for Christian liberals and reform-orientated parents with Jewish roots. Petersen called his school ideal “free general elementary school according to the principles of New Education”. Petersen’s school ideal of institutional education was the comprehensive school from kindergarten up to university entrance.

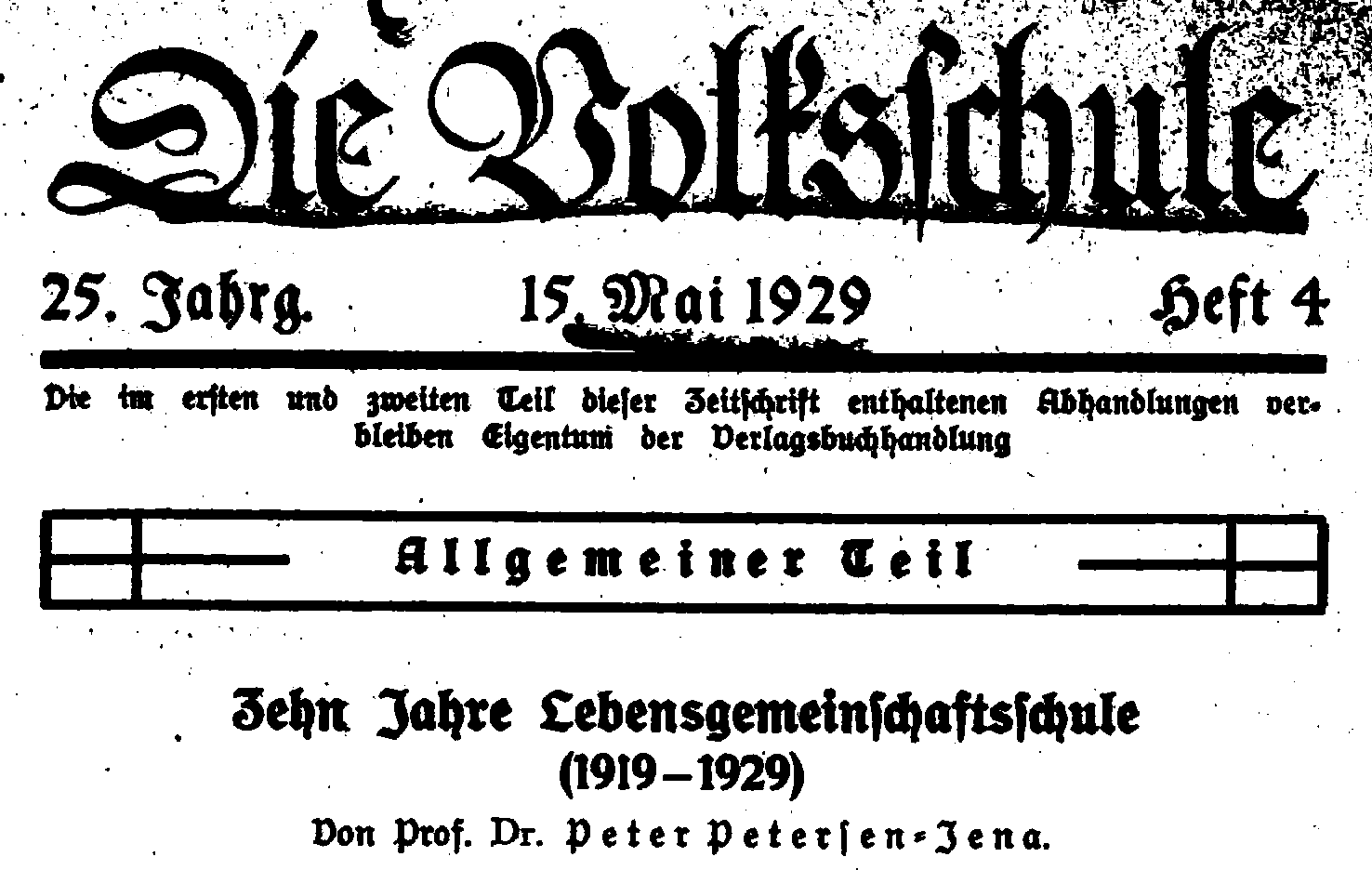

“Free” meant: a family school co-responsible by the parents. However, during the Weimar Republic and the “Third Reich”, he was only allowed to run an experimental elementary school for pupils in grades 1 to 8. Its starting point was the reform movement of the “Lebensgemeinschaftschulen” and the idea of training elementary school teachers (Volksschullehrer) at the university; the traditional teacher training seminars are known to have a much lower scientific level. As late as 1929, he had celebrated the socialist “Lebensgemeinschaftsschule” (Life Community School) on the occasion of their tenth anniversary.

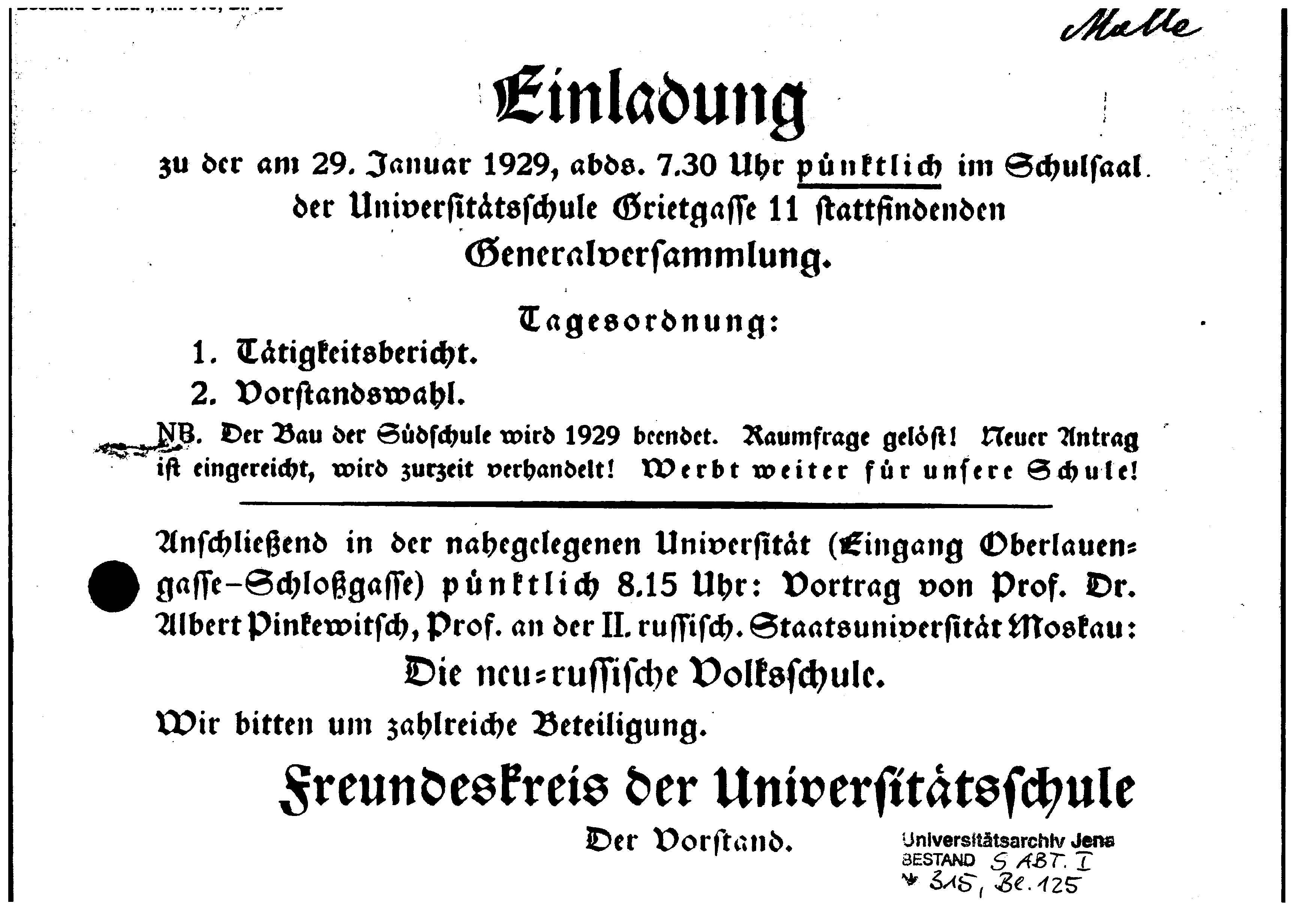

Figure 2: Peter Petersen pays tribute to the tenth anniversary of the socialist “Lebensgemeinschaftsschule” (Life Community School) in the magazine “Die Volksschule”, in 1929.

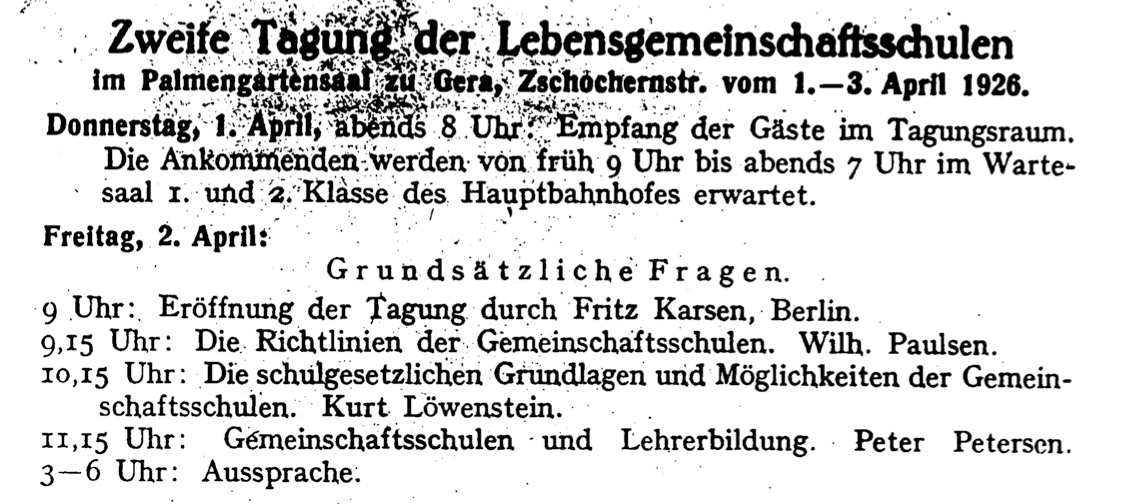

In 1926, Petersen gave one of the keynote speeches at the annual conference of the “Lebensgemeinschaftsschule” in Gera, – together with the leading Marxist pedagogues of the Berlin school reform movement Fritz Karsen, Wilhelm Paulsen and Kurt Löwenstein.

Figure 3: Petersen in the circle of leading Marxist school reformers, Gera 1926. Program announcement. Magazine “Lebensgemeinschaftsschule”, 3, 1926, p. 33.

Nazi pedagogues in Jena were right in this respect when, after 1933, they mentioned Petersen’s commitment to international understanding in the 1920s, his liberal pedagogy and his proximity to left-wing circles, whereas Peter Petersen, after Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor, tried to make this impression forgotten by his new identification with the “national political revolution”. Petersen’s journalistic demonstration of his intellectual proximity to the Nazi pedagogue Krieck and his students was striking. For example, when he tried to prove that the “political-soldiary” was relevant to his own educational ideas (Petersen, 1934a; critical report of the NSLB district administration Jena, in Retter, 1996b, p. 157f.).

Up to the fourth edition in 1932, the work Petersen had made known to the public and later called “Der Kleine Jenaplan” was also internationally presentable, while the 6th/7th edition in 1936 showed considerable adaptations to National Socialism. After the war, Petersen tried to reverse this in further editions of this booklet, but he was by no means successful to remove all traces of the now undesirable past (Retter, 2010, pp. 230-233).

From 1933, Petersen incorporated the new National Socialist character of the public school system into his school, such as the Nazi school celebration at the beginning of the week (with the hoisting of the flag), the Hitler picture, the Hitler salute at the beginning of lessons. The questionable assertion that his pedagogy had “always” been open to the “demands of [racial] hygiene, eugenics, race doctrine, and hereditary science” (Petersen, 1934b, p. 3f.) did not, however, lead to his physically and mentally disabled and developmentally disturbed children leaving his school – on the contrary, he had such children in his school even after 1933 (ibid., p. 60). Here, in the core area of education, Petersen’s school differed significantly from the Nazi school policy of excluding those elements of education and life opportunities that were undesirable in the Nazi “Volksgemein-schaft”:

The “’Law against the overcrowding of German schools and universities’, which was passed on April 25, 1933, introduced ‘race‘ as a criterion for access to secondary schools and university studies. The proportion of Jewish pupils and students in the entire school and student body was no longer allowed to exceed the Jewish proportion in the total population of just under one percent. As a result, the number of Jewish pupils in public schools halved until 1935, before tending towards zero after 1938.”i

While the Nazis restricted educational opportunities for Jewish children from the beginning, Petersen encouraged them (as the examples of Elisabeth Scheinok and Margot Reinhardt show). We have to see: Under Nazi rule Petersen pursued a strategy that only seemed to promise him success if he behaved completely differently in different contexts.

In the review of an anti-Semitic writing in 1933, Petersen had described the “nature” of the “Jews living in Germany” as “decomposing, flattening, even poisoning for us”. He demanded their “return to their own way of life”,”which had already been done with the best success in Zionism” (Petersen, 1933). With this text Petersen produced the worst anti-Semitism. His recommendation to remove Jews from Germany by referring to the Zionist movement was in line with the Nazi policy of separation.

The obvious question is how this recommendation influenced everyday life of the University School. Whether a student was Jewish or only “half-Jewish” (first degree race mixed) or “quarter-Jewish” (second degree race-mixed) in Nazi classification was irrelevant to an anti-Semitic headmaster who hated anything Jewish. If the “racist” Petersen had wanted to make the University School “Jew-clean”, he would not have accepted Elisabeth Scheinok, whose parents were Jews from Poland, into his school in the first place, nor the (partly) Jewish children of those parents with whom he had closer contact, such as the Eppenstein and Wandersleb families.

The dissertation of the Polish Jew Tonja Lewit on “The transformation of Jewish national education in Poland” would never have been promoted by an anti-Semite Petersen. His report of February 28, 1928, appreciatively emphasized in Lewit’s study that the development of a “Jewish-secular school” in contrast to the orthodox-national Cheder was a new topic to which the author had devoted herself” with effort and prudence”,”with diligence and dedication”. The new Jewish school system in Poland appears as “a link among the manifold new developments in the field of education in Europe after the World War” (UAJ: stock M, No. 596). As little attention is paid to the author, who was a victim of the Holocaust, by today’s reception of Petersen’s work, so exclusively those expert opinions are cited in which Petersen praised the dissertations of young Nazis, such as the work of Hans-Joachim Düning (UAJ: stock M, No. 601).

While in the GDR reform educational concepts in favour of the socialist uniform school were forbidden, in West Germany (Federal Republic) a renaissance of the “Reform Pedagogy” (internationally also known as “Progressive Education” or “New Education”) of the 1920s took place in the course of about three decades after the Second World War. From the 1970s onwards, the discussion about Petersen’s problematic role in the Hitler state began to become a permanent topic of German educational science. During the Weimar Republic, Petersen was highly regarded both in Germany and internationally for his efforts to promote a “New European Education Movement” that would unite peoples. Recent research has shown the extent to which his publications were influenced by National Socialism, both through his commitment to Nazi ideology and his contacts with Nazi organizations.

Petersen became a member of the NSLB on April 1, 1934; only in this way did he have a chance to interest Nazi functionaries in his pedagogy. Even though he and his wife Else did not belong to the NSDAP, it is striking that Petersen’s close circle of students had joined the party (NSDAP). Heinrich Döpp-Vorwald, Herbert Ruppert and Johann Dietz had completed this step on May 1, 1933, and Christoph Carstensen, Petersen’s assistant from April 1, 1938 to July 1940, did not join the NSDAP. He already had joined the SS on November 4, 1933. For others, such as Käthe Heinze, Herbert Sailer, Karl Knoop, joining the party was only possible after the ban on admission had been lifted in 1937 and was then carried out. Some of the aforementioned also belonged to other party organizations, such as the SA (Döpp-Vorwald, Sailer, Knoop) or the SS (Ruppert, Carstensen, Knoop). Petersen could only be right. For without this needing to be mentioned, he thus possessed a “brown” figurehead, which on the one hand helped to compensate for his own non-membership in the party, and on the other hand was good for political contacts in higher positions (Retter, 2007, p. 336).

The fact that Petersen behaved extremely differently towards different groups of people at the same time in the same time context does not indicate that he actually possessed any valid political conviction that he claimed to represent. It can be assumed that he used his language in public in an extremely goal-oriented manner to achieve his plans. His primary interest was to preserve his school, which should be (and was) a safe educational place for parents with their children, independent of politics. At the same time, Petersen wanted to help the Jenaplan gain recognition in the respective political system. This was a balancing act that was bound to fail. Petersen’s need for personal recognition and his efforts to expand his options for action were exorbitant. The contradictions, temptations and dilemmas Petersen faced in this process have been revealed by Petersen research of the last decades. His dubious journalism and his cooperation with Nazi officials make the historical retrospect on Petersen appear ambivalent. In the long run, his strategies of power did more harm than good to the Jenaplan. Such an attempt at interpretation certainly does not make his racist texts any better, but it does explain some of his behaviour. It remains to be noted: Petersen never removed a child from his University School. He never refused to admit a Jewish child or a child of Jewish origin to his University School. Some former students of his school, whose parents or they themselves were threatened by Nazi measures, have remained grateful to him.

3. Trigger, Course and Highlights of the Recent Petersen Debate

A new examination of the topic “Petersen and National Socialism” began with the publication of a documentation volume (2008) by Prof. Dr. Benjamin Ortmeyer, University of Frankfurt a.M. – as part of his habilitation thesis (Ortmeyer, 2009). The documentation of all texts by Petersen 1933-45 contaminated by Nazi ideology – including previously unknown texts with particularly repulsive racism – met Jena unprepared. But it also caused a sensation throughout Germany. For none of the (relatively short) texts in which Petersen produced racist Nazi ideology was known until then. They are also missing in the Petersen Complete Bibliography by Walter Stallmeister (1999). The public distancing of Petersen’s identification with the Nazi system was an imperative for the Jenaplanschule Jena (as well as for other schools that worked according to the Jenaplan). Not Petersen’s text production of the Nazi era, but the Jenaplan of the Weimar Republic in its original form became the basis of the modern school concept.

Ortmeyer’s declared goal from 2009 was to inform the population, especially in the city of Jena, about the fact that Petersen was an anti-Semite and racist. Connected with this was the demand to give the Petersenplatz in Jena a different name. There should be no place for a racist in Jena’s culture of memory. One can read about the dispute about Petersen in Jena, today in press reports, especially in the Ostthüringer Zeitung (OTZ) from 2009 to 2011 in documentaries, also online. Ten years have passed since the highlights of this discussion, and there is calm on all fronts of the former dispute. There is no need in Jena to remember this. The sequence of events in Jena 2009-2011, which led to the renaming of Petersenplatz, can be summarized in the following points:

In autumn 2009, the city of Jena organized forums (panel discussions) open to the public, to which a number of researchers from outside were invited, including Ortmeyer (Frankfurt a.M.), Schwan (Osnabrück), Retter (Braunschweig). Other scientists who presented statements of their views on the “Petersen case” also took part in the public discussion.

On November 4-5, 2010, the “Petersen-Workshop” took place in Jena: a scientific conference (with audience participation) with the lectures of a wider range of experts. Their presentations were published in the conference report (Fauser, John, & Stutz, 2012). Schwan and Ortmeyer had cancelled their participation after the conference. That was a reaction to the book about the Jena University School (Retter, 2010), which was published two weeks earlier. On November 29, 2010 Schwan wrote a devastating “analysis” of the book, which was at the heart of the texts of the “documents” that the GEW published in February 2011 (see Schwan, 2011). The book and Schwan’s paper were not mentioned at the Petersen Workshop, but the participants were aware of them. – On December 14, 2010, there was no majority in the Cultural Committee of the City of Jena for the proposal to rename Petersenplatz, but a stalemate of five approving and five non-approving votes. – On January 12, 2011, Prof. Dr. Reinhard Schramm, the then second and now first chairman of the Jewish Community of Thuringia, commented: “Petersen’s anti-Semitism is openly apparent, so that renaming Petersenplatz is a matter of the moment. Nothing could be objected to renaming the square with the term “Jenaplan”. – On 16 March 2011, the Jena City Council decided by a majority vote to rename Petersenplatz. – On March 22, 2011, the Cultural Committee of the City of Jena decided by a majority vote that the new name of the former Petersenplatz would now be “Jenaplan”.

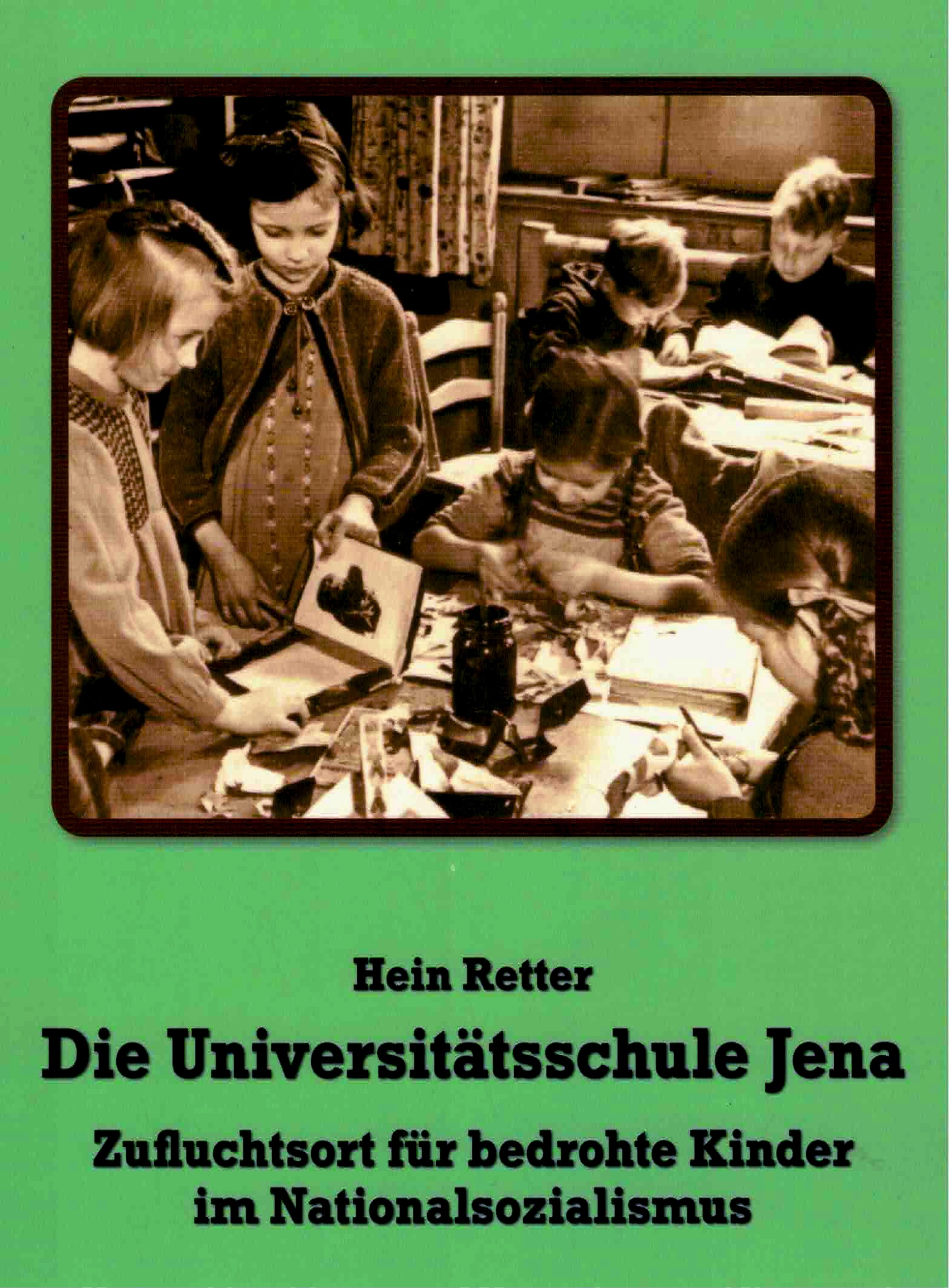

Was the Petersen case closed? How has the evaluation of the “Jenaplan” changed, since its author, Peter Petersen, today marked as racist and anti-Semitic, usually only causes eloquent silence among educationalists? The question arises, since the volume “Die Universitätsschule Jena – Zufluchtsort für bedrohte Kinder im Nationalsozialismus” (The Jena University School – Refuge for Children at Risk under National Socialism [Retter, 2010]), contributed significantly to the heated discussion in Jena ten years ago. Rarely has a book about the situation of parents and children in a school during the Nazi era met with such strong rejection.

It was about families who were not followers of Adolf Hitler’s idea of a pure racial community in the service of the NS: In Petersen’s university school, these were families with Jewish, socialist or Protestant faithful belief (as well as families with a physically or mentally handicapped child). While the majority of these children had already attended Petersen’s school for several years under democratic conditions before Hitler came to power, they became “enemies of the people” under the Hitler dictatorship, and the Nazis were increasingly fighting them.

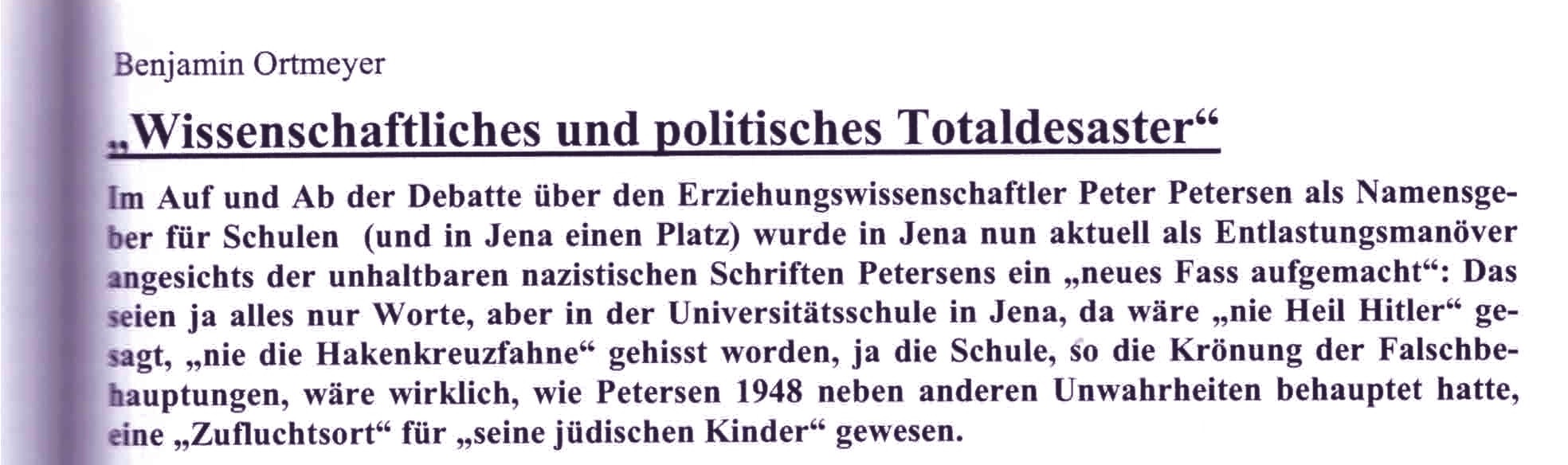

Ten years ago, nobody wanted to say that the volume made a relevant contribution to research. Today one can talk about it. Benjamin Ortmeyer (2008), whose documentation of Petersen’s publications during the Nazi dictatorship was decisive for the Petersen debate in Jena, reacted to the book (Retter, 2010) by calling the volume a “scientific and political total disaster”, taking over a statement by Torsten Schwan:

Figure 5: Quote from B. Ortmeyer, in Dokumente, 2011, p.163: Hein Retter’s book (2010) as “scientific and political total disaster”.

Dr. Torsten Schwan had written about the criticized book: “The distortion of the actual historical situation made by Retter is – unfortunately this must be named so clearly – simply grotesque” (Schwan, in Dokumente, 2011, p. 136). And: “As shamelessly as in this book – this has been shown in various places – repression and instrumentalization has not been practiced in pedagogy for decades. […] How serious the damage caused by his unacceptable instrumentalisations is for the Jenaplan pedagogy, but also for the city of Jena, will only become clear in the future” (Schwan, ibid. p. 154).

I think, ten years were sufficient to establish how resounding the “damage” of the book of the “shameless” author had done was in fact. The interested reader will find the “shameless” result at the end of this article (see ANNEX). In the campaign against the book (see Figure 5), a far-reaching catalogue of assertions was made, which can be summarised in three points:

1/ The Reform Pedagogue Petersen was a Racist and Anti-Semite.

2/ There were no children in the Jena University School under Petersen’s leadership who were racially or politically endangered or threatened during National Socialism, nor were there children of Jewish parents or endangered children with Jewish roots. As far as partly Jewish children attended the Petersenschule, they did not have to fear any threat from Nazi legislation. The Jena University School was neither a place of “refuge” nor a place of protection for allegedly “threatened” children who attended this school. Petersen’s school, which had existed as an experimental school since 1924 and became the birthplace of the pedagogical reform model “Jena Plan”, was rather attended by children of high-ranking Nazis in the “Third Reich”; likewise, a large number of the teachers were Nazis.

3/ In his lousy work, which “is ultimately so shamelessly instrumentalized, so inadmissibly simplified and at the same time does not show the trace of a critical claim” (Schwan, in Dokumente, 2011, p. 157), Hein Retter tells fairy tales and fictions about Petersen and his school in order to stage a “revisionist rescue of Petersen’s honour” (ibid.).

4. The Role of the Teachers’ Union, “Gewerkschaft Erziehung und Wissenschaft (GEW)”

After ten years, we have to report what has become of the “total disaster” that the author Hein Retter was certified to have suffered. Things really didn’t look good for him in 2010. The spokespersons of the debate had the support of the local press (OTZ) and the GEW: Solidarity support was provided by the GEW Thuringia, the GEW District Association Jena and the GEW-Studis of the Friedrich Schiller University. They all acted as editors of a “documentation” (2011), flanked by the GEW main journal “Erziehung und Wissenschaft” (E&W), owned by the GEW umbrella organisation (headquarter: Frankfurt a.M.).

The brochure also contained photos of a poster campaign with Petersen quotations, which had been organized by the “GEW-Studis” of the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena under the direction of Mike Niederstraßer. Also published there is the correspondence that Ortmeyer and Schwan had with Jena’s Lord Mayor Dr. Albrecht Schröter (SPD) when they withdrew their participation in the Petersen Workshop Jena (November 4-5, 2010). Although forgotten today, it is an interesting reader in terms of contemporary history. Here, to criticize the book about the Jena University School (Retter, 2010) was not enough for the opponents. They needed an even stronger argument for their “shooting out” and found it in the accusation of historical revisionism (Geschichtsrevisionismus). “It is less about Petersen than about historical revisionism” (Ortmeyer, quoted, in Dokumente, 2011, p. 12). And: “But the hardest and best proven reproach of Torsten Schwan against Hein Retter‘s writing is the reproach of historical revisionism” (ibid., p. 164). What was meant was: Hein Retter is a history forger and denied the Holocaust.

“Holocaust denial” is the extensive trivialisation or denial of the National Socialist genocide of the European Jews. In German jurisdiction this is a punishable offence. The Holocaust has played a role in our family till today, but in a manner that we feel to be an obligation to keep the cry “Auschwitz, never again!” always alive in our consciousness (Retter, 2011, p. 264; Retter, 2017, p. 121f.). For this reason, Petersen’s conduct can in many respects only be regarded as questionable. But if this warning becomes a puffery, as was the case in the Jena Petersen discussion, then one cannot remain silent. I think, it is difficult to present contemporary history with a pure heart when such scholars uphold the argument, “Six million murdered in the Nazi genocide” only to make their own assertions unassailable, but suppressing the concrete fate of those persecuted by the Nazi regime, when these people are grateful for the protection they received from the Petersen University School during the Hitler dictatorship.

The GEW organ “E&W” (Frankfurt a.M.) had published in its November 2010 issue an essay by Karl-Heinz Heinemann, entitled “Petersens Weg zu Hitler” [Petersen’s path to Hitler] (Heinemann, 2010, pp. 22-23). Certainly the Petersen Workshop in Jena on November 4-5, 2010 was to be accompanied by a challenging message from the GEW organ. To illustrate the text, a photo was presented with the explanation: “Pedagogy under the swastika: Most schools were under Nazi influence – including the Jena Plan model schools. The teacher-student relationship reflected the relationship between ‘leader and followers'” (see below, Figure 7):

Figure 7: Photo of an alleged Jenaplan school during the Nazi dictatorship.

Notes (by Hein Retter): 1/The photo obviously does not show a Jenaplan school. 2/”Jena-Plan model schools” did not exist in the NS state. 3/The description of the photo (“Mediennummer 3522388 © picture-alliance / akg-images”) by “dpa Picture-Alliance GmbH” is: Boys’ class with teacher in the classroom, photo, without place and year (Germany, 1935); see also: Heinemann (2010).

Comment 2020: How is it that a photo is supposed to say something typical about Jenaplan pedagogy but does not show a Jenaplan school? How can the picture come from a Jenaplan school if the picture agency neither claims this nor the viewer finds signs of it? We see a classroom of the traditional kind: with screwed benches, without freely adjustable tables. This is traditional teaching in a classroom that Jenaplan radically changed through inter-year study groups. An inquiry to this effect made to the editorial staff of E&W in late autumn 2010 could not be clarified there. But they were willing to accept that the photo did not come from a Jenaplan school.

How is it that a photo is supposed to say something typical about Jenaplan pedagogy but does not show a Jenaplan school? We see a classroom of the traditional kind: with screwed benches, without freely adjustable tables. This is traditional teaching in a classroom that Jenaplan radically changed through inter-year study groups. An inquiry to this effect made to the editorial staff of E&W in late autumn 2010 could not be clarified there. But they were willing to accept that the photo did not come from a Jenaplan school. The assertion that Jenaplan model schools existed during the Nazi era is incorrect. In Westphalia in 1934-35, there were school experiments with home-bound group lessons, behind which Petersen’s Jenaplan pedagogy hid, but the term “Jenaplan” was not allowed to appear officially, and “Nazi model schools” they were by no means, as the critical report of the ministerial official from Berlin, Dr. Voigtländer, stated in his report on Petersen’s “Pedagogical Week” of May 22-26, 1934, in Rahden/Westphalia. The expert from the Reich Ministry of Education (Berlin) emphasized “that Petersen’s pedagogy cannot provide the basis for a National Socialist school reform” […] “It is known that Prof. Petersen only formally recognized the state as the schoolmaster. […] Rather, one must “avert the dangers that may arise from the apolitical and formal character of Jena’s pedagogy” (in Retter, 1996b, pp. 291-293).

Nowhere else than at that conference in Rahden in 1934 did Petersen in the Hitler state publicly betray his ideals of freedom and humanity from the Weimar Republic, and this for a plate of lentils of the expected expansion of the Jena Plan – and of course also to preserve his own school. The conference in Rahden in 1934 was a major event, which in its appearance naturally paid homage to National Socialism in all its form.

Once again Petersen was fortunate to be one of the main speakers at the VI International Congress on Moral Education in Krakow in September 1934. Here he was enthusiastic about the “national political” change in the German Reich on the basis of “landscape and race, language and myth” (Petersen, 1935, p. 214). But once again, for Petersen, supposed success turned into obvious failure. With the decree of February 3, 1936, the Reich Ministry of Education banned the further spread of the school experiments. In the district of Lübbecke/Westphalia, this led to the fact that in places where the school organization already corresponded to the Jenaplan, it was soon switched back to “normal operation”. Petersen’s University School in Jena was allowed to continue to exist, although an official school visit in 1935 did not give it a particularly good report card.

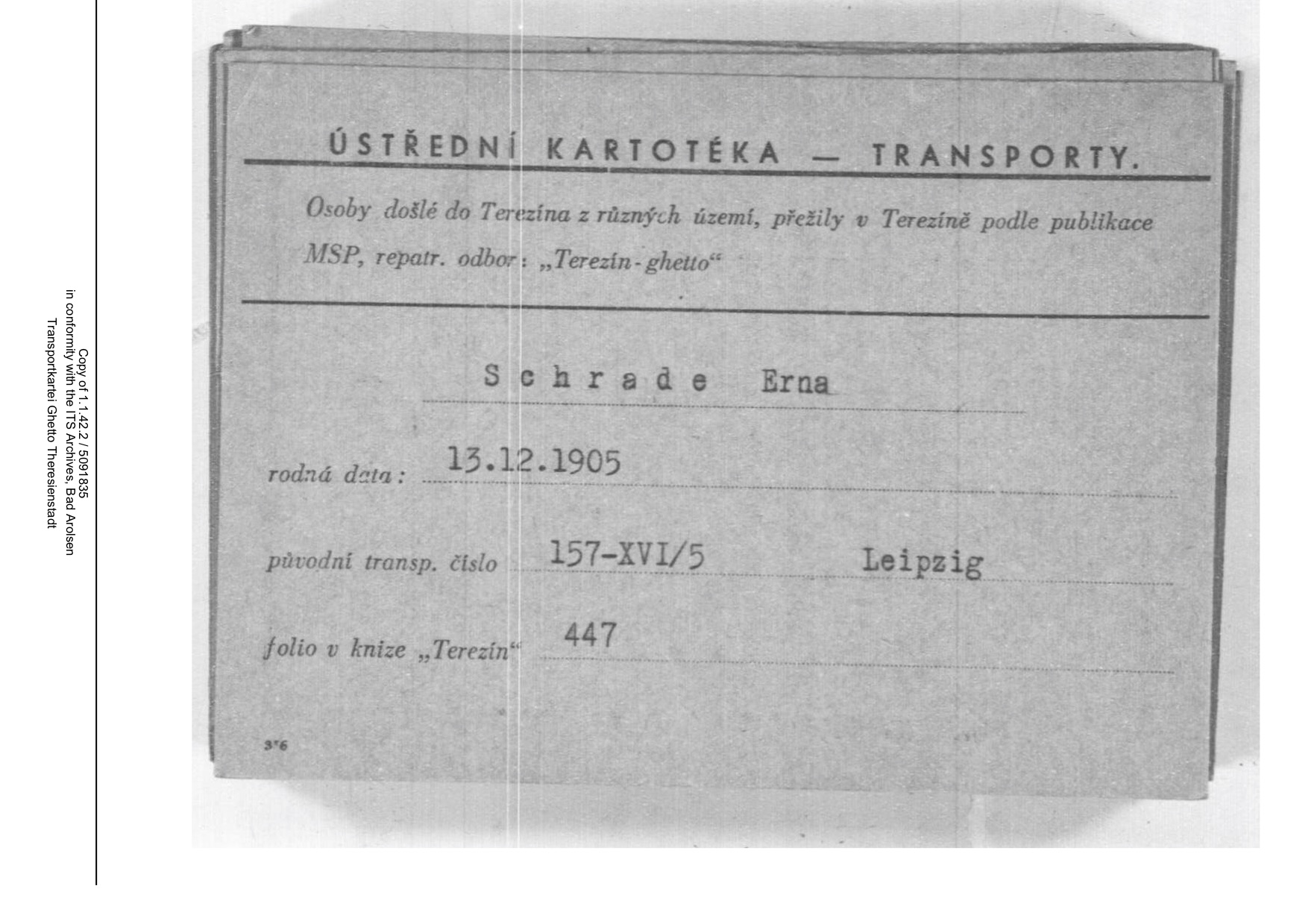

In the first months of 2011, a letter to the editor campaign against the reform pedagogue Petersen took place in the GEW press organ “Education and Science” (E&W). It supported the demand to rename the Petersenplatz in Jena. So it was claimed, referring to Hein Retter and his book (2010), that “recently Jewish children at Petersen’s school during the Nazi era must be invented”. (Schwan, in: E&W, 2/2011, p. 34). It is clear to every reader of the book (2010) that the term “Jewish children” – as well as the subchapter in the book (2010) “Children from Jewish families” – served as a collective term for children from partly Jewish families. Cornelia Cotton, Rolf Schrade, Margot Pampel, had confirmed in their reports: in the everyday life of the Nazi regime one was stamped as a Jew, no matter what classification level of the racial laws one belonged to. Schwan, however, had to give the term “Jewish” the meaning “fully Jewish” to be able to say that Jewish children were “invented” here. Rolf Schrade contradicted him as a directly affected person (see below, Figure 8a+b).

The former Petersen student, Prof. Dr. Rolf Schrade, wrote an “open letter” in February 2011 which was sent to several persons and institutions, also to the GEW magazine E&W. Schrade referred directly to Torsten Schwan’s statement about the allegedly “invented Jewish children”. Anyone who thought that the GEW editors would immediately print Schrade’s letter in the next issue was mistaken. In March 2011, a statement by the “GEW-Studis” of the University of Jena appeared in E&W. Their message was that “no evidence had ever been presented for the fairy tale of the rescued ‘Jewish children'” (E&W, 3/2011, p. 35). Finally, in May 2011 Schrade’s letter to the editor was published, but in a revised form at the end of the letter. Schrade’s original letter, which referred directly to Torsten Schwan’s statement, read (See also in German, the original and the changed version: Retter, 2012, p. 334):

I read with great shock in a reader’s letter from Torsten Schwan that the stay of Jewish children at the Petersen School in Jena, about which Prof. Hein Retter reports in his book “Die Universitätsschule Jena im NS”, was an invention of the author. But there were Jewish children at the Petersen School: I am one of them. Born in 1934, I was regarded as half Jewish during the Nazi era and despite this “flaw” I was able to attend precisely that school from 1940 until the end of the war in 1945. My Jewish mother Erna Schrade was deported to the concentration camp Theresienstadt during that time. My father, then head of personnel and later head of planning at Carl Zeiss Jena, who had refused to divorce my mother, was “transferred” to a labor camp in Merseburg in 1944. My parents miraculously survived the concentration camp. I owe it to courageous people like Petersen who, through their have protected unconventional behaviour.

I think – and this I would like to address to the writer of the address reader’s letter – that belongs to a historical view, to actually consider all sides of a person and an event. A polemical one-sided representation, as he gives it, does not damage only the reputation of the reform pedagogue Petersen, but also insults those persons who endured the suffering and injustice of the Nazi era. Rolf Schrade, Mahlow.

Prof. Dr. phil. Dr. h.c. Rolf Schrade, Berliner Str. 25, 15831 Mahlow. Open letter February 20, 2011.

Figure 8a: Open letter from Prof. Dr. Rolf Schrade, .2011, February (Here translated into English).

The end of Schrade’s letter I have put in italics (see above) to show what the E&W editorial team made of it: The posthumous thanks to Petersen and Schrade’s criticism of GEW member Schwan have been deleted. In the form published by E&W in the issue May 2011, p. 43, the text finished (in original in German):

That I too survived in Jena is thanks to courageous people like Petersen, who protected me with their unconventional behaviour. A historical view also includes actually considering all sides of a person and an event. A polemical one-sided portrayal also insults the people who had to endure the suffering and crimes of the Nazi era.

Figure 8b: The last sentences of the “open letter” by Rolf Schrade changed and published by the GEW editors, E&W, 5/2011, p. 43 (adopted by Retter, 2012, p. 334).

5. Aftermath of the Petersen Debate – An Overview of Further Events

After “Petersen experts” branded the book about the Jena University School (Retter, 2010) as a “total disaster”, the following is an overview of how the volume became the starting point for new developments, events and research findings.

While critics claimed that the controversial book, which appeared in October 2010, was written “to ensure the preservation of ‘Petersen-Platz'” (in Dokumente, 2011, p. 157; p. 163), its author Hein Retter had stressed in February 2010 that Petersen “should not be a namesake of a street or a square because of his concentration camp lectures and his racist texts”. The statement was printed in the “Ostthüringer Zeitung” (OTZ), as Figure 9 shows.

Year 2011

Figure 10: “Stolperstein” / Stumbling stone/ for Gitta Reinhardt, née Czerwinska, murdered in Auschwitz, May 2, 1943.

On June 18, 2011, a “Stolperstein” (commemorating brass plaque, lit. “stumbling stone”) was set in Jena in front of the last residence of Gitta Reinhardt, “Volljüdin” /Full Jewish (Nazi classification), murdered in Auschwitz, on the occasion of Holocaust remembrance. Her daughter Margot Reinhardt, married Pampel, was a student at the University School. Margot’s daughter Felicity Z walf, who came from Melbourne, spoke about her grandmother words of remembrance, as well as about the life and survival of Margot (Felicity’s mother) under Nazi rule in Jena. The identification of Margot Reinhardt as a Jena Holocaust victim and the identification of her daughter as a student of the Petersen School would have been quite sufficient to justify the book about Petersen’s University School. But for the critics the elaborate research work was a “total disaster”, the “fairy tale of the Jewish children” the “GEW-Studis” wrote (E&W 3/2011, p. 35).

Year 2012

In spring 2012, the lectures of the Jena Petersen Workshop of 2010 were published, and the volume continues to determine the current state of discussion about Petersen in educational science (Fauser, John, & Stutz, 2012).

Figure 11: Cover of the conference proceedings of the “Petersen Workshop” in Jena November 4-5, 2011, edited by Peter Fauser, Jürgen John and Rüdiger Stutz, with the collaboration of Christian Faludi. Title in English: Peter Petersen and the Jenaplan Pedagogy. Historical and current perspectives. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012.

Year 2013

On November 14, 2013, a wall sculpture was inaugurated in the Volkshaus in Jena in memory of Hildegard Grebe-Grottewitz, who worked as a dance and gymnastics teacher in Jena from 1928 to 1938; as a half-Jew, her public appearance in 1937 was prohibited by the NSDAP in Jena. Her application to the Nazi authorities to be allowed to enter a second marriage after her divorce was probably not granted; she was threatened with sterilization; she fled to Berlin with her life partner and her daughter, Cornelia, born 1927 Cotton, 2008, p. 111). Cornelia Grebe had attended University School from 1934-38. In Berlin then, the family had to live a life of anonymity in order not to be discovered; the marriage did not take place until after the end of the war (see Jüdisches Leben, 2015, pp. 267-269). Cornelia Cotton, née Grebe, who had donated the sculpture. came to Jena from the USA on occasion of the memorial service for her mother. Years earlier, in her life review (Cotton, 2008), she had already reported on her upbringing in Jena during the Nazi era – with gratitude for her time at University School, where she felt safe, which was not always the case on the streets. A contribution by Gisela Horn on “Women in Jena” had recalled the fate of Cornelia’s mother, Hildegard Grebe-Grottewitz (Horn, 2007, p. 58f.).

Year 2015

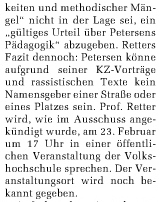

In 2015, the volume “Jüdische Lebenswege in Jena”, edited by the Jena City Archive and comprising over 600 pages, was published under the editorial direction of Constanze Mann. The documentation contains “Memories, Fragments, Traces” (subtitle). It was the continuation of the first book about Jewish Life in Jena, published by the “Jena Arbeitskreis Judentum” in 1998. Interesting for us: What role does the recent Jena discussion about Petersen play?

- The “quarrel about Petersen”, which shook Jena before and after 2010, is completely unmentioned in the volume “Jüdische Lebenswege”.

- The term “Jewish” in the title of the volume is used as a generic term for persons who were not only full Jews in the sense of the Nazi racial laws, but also including persons of Jewish origin. – This corresponds completely with the view of the book by Hein Retter (2010).

- For the first time in the Jena commemorative literature about victims of National Socialism, the respective authors of the contributions mention Jewish and partly Jewish families in larger numbers whose children attended “Peter Petersen’s University School”.

- In the literature and source references of the respective contributions, the controversial book of 2010, “Hein Retter, Die Universitätsschule Jena…”, is regularly listed.

- Among other things, the Jena documentation mentions that Petersen’s sons had lived in the house of the “Volljuden” (Nazi classification) Otto Eppenstein since 1931 – after the remarriage of Petersen’s first wife (divorced in 1927), Gertrud, nee Zoder (1892-1958), with Otto Eppenstein (1876-1942), who also entered into the second marriage (Jüdische Lebenswege, 2015, p. 235; see Retter, 2007, pp. 158f.); the friendship of the Petersen and Eppenstein families lasted since 1924, when the former moved from Hamburg to Jena due to Peter Petersen’s appointment to the Thuringian State University.

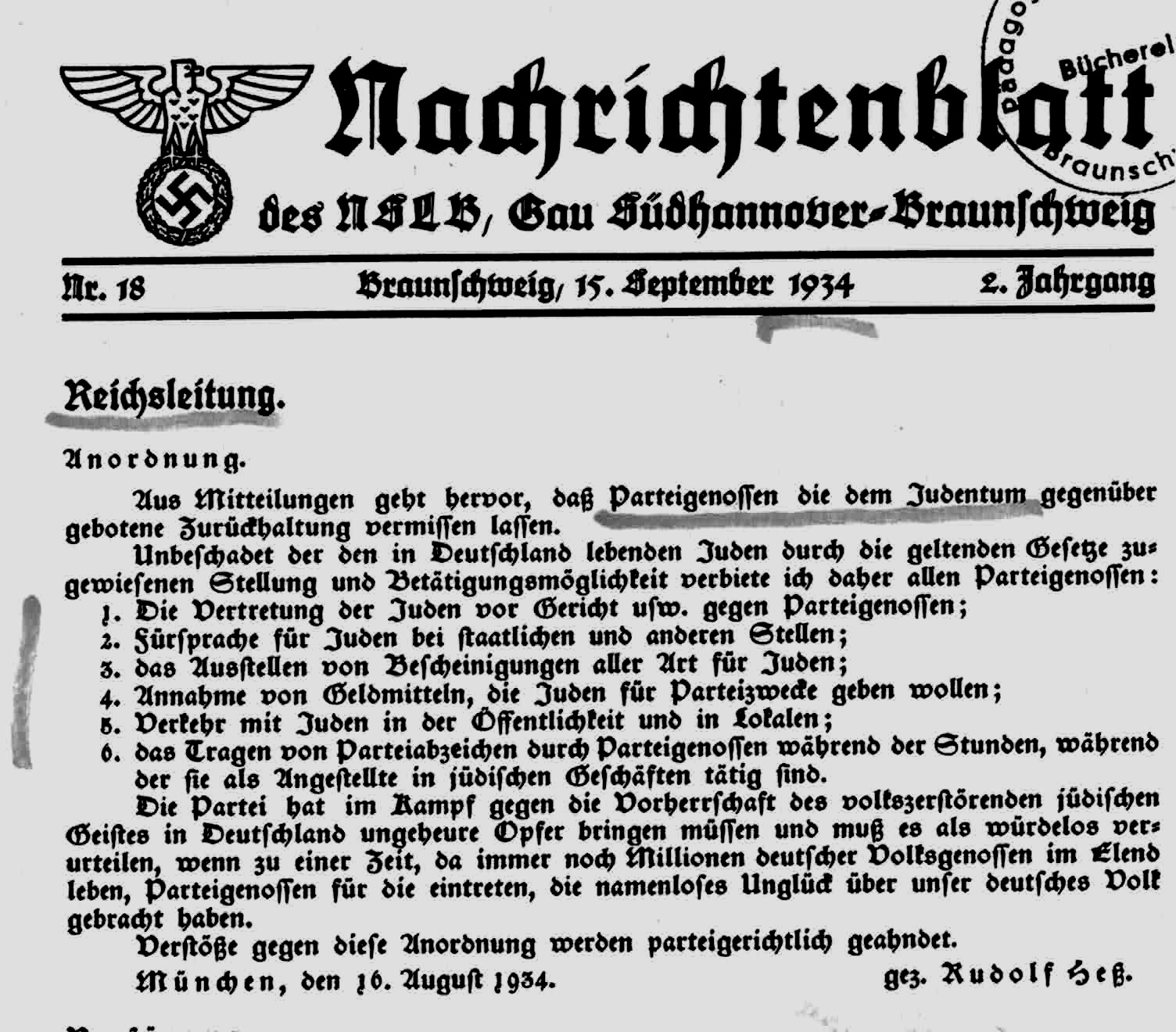

Figure 13: Avoidance of Jews – Order for party members, by the Deputy Führer, Rudolf Hess (Reichsleitung), September 15, 1934.

Contacts with Jews in everyday life had been strictly regulated for members of the NSDAP in 1934 by the deputy leader, Rudolf Hess (see figure 13). NSDAP members were forbidden: “1. to represent Jews in court etc. against party members; 2. to intercede for Jews in state and other offices; 3. to issue certificates of any kind for Jews; 4. to accept funds which Jews want to give for party purposes; 5. to have social interaction with Jews in public and in restaurants; 6. to wear party badges by party members during the hours when they are employed as employees in Jewish shops.” Petersen was not a member of the NSDAP, but as a member of the NSLB (since April 1, 1934), so he belonged to an important subdivision of the Hitler Party. That the order should also apply to NSLB members suggests its publication in the NSLB Newletter. Petersen’s handling of this precarious situation plays a role in the historical judgment of him. I have no information that he ever visited the house Eppenstein in Jena, Otto-Devrien-Straße 16, during the Nazi dictatorship. His two sons (they became university students in the thirties) and his wife Gertrud from his first marriage lived there, apart from his former family friendship with Otto Eppenstein.

Year 2016

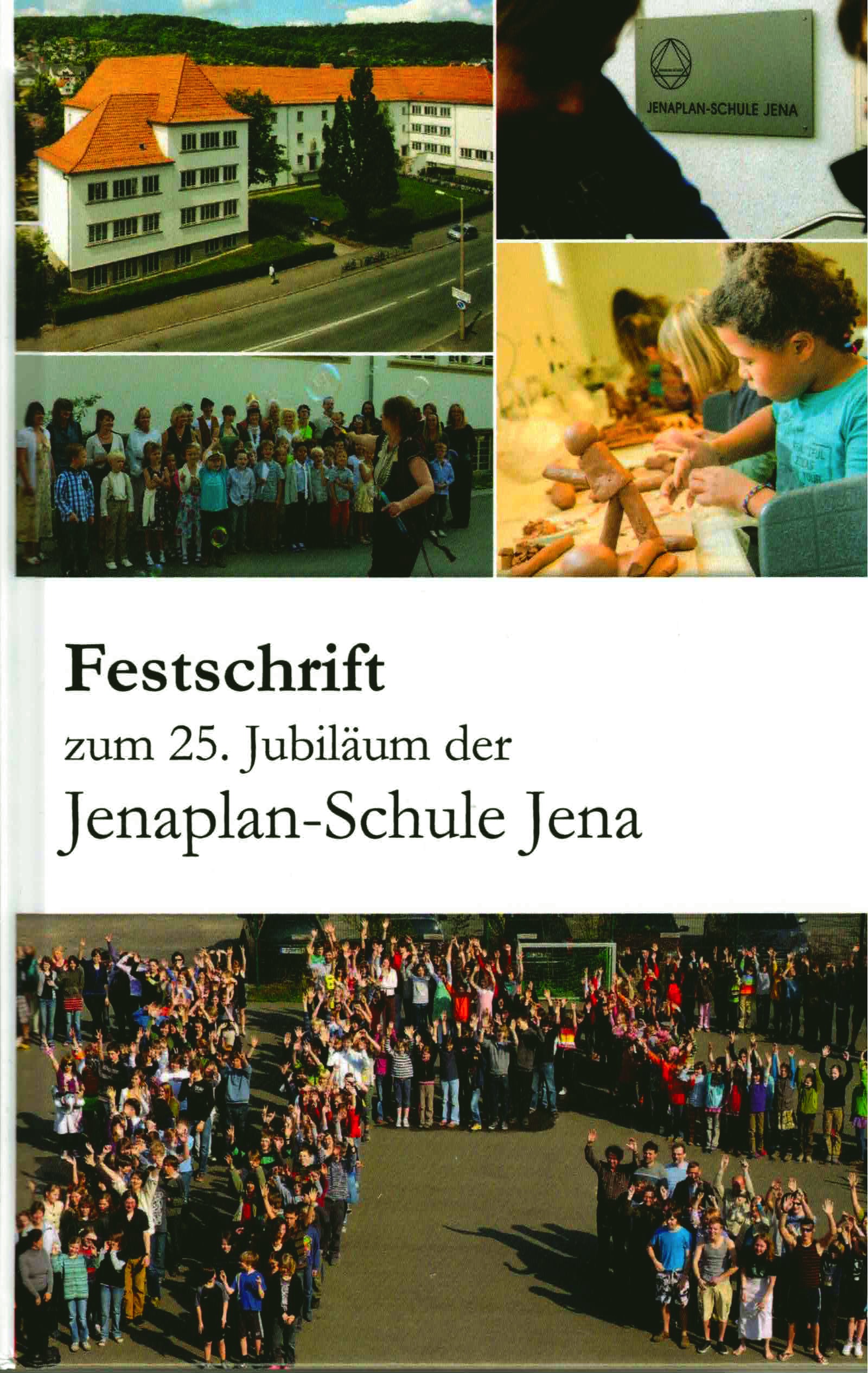

On May 27, 2016, a ceremony took place on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Jenaplanschule Jena. Present among the guests of honor was Margot Pampel, 94, in a wheelchair. On the occasion of the anniversary, she had come from Australia to Germany on a last trip accompanied by her daughter. The day before, the Lord Mayor of the City of Jena, Dr. Albrecht Schröter, gave a reception for Margot Pampel with guests including headmaster Frank Ahrens (Jenaplanschule Jena) and Ilja Rabinovitch, from the Jewish Community in Jena.

On the day of the ceremony (May 27, 2016) the school’s “Festschrift” was published, which also contains the greetings of Claudia Cotton, Margot Pampel and Rolf Schrade. The three very old people from the USA, Australia and Germany recalled their schooldays at the University School (see ANNEX).

Figure 15: Ostthüringer Zeitung on May 30, 2016: Photo and report on the visit of Margot Pampel from Australia on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Jenaplanschule Jena.

Figure 15: Ostthüringer Zeitung on May 30, 2016: Photo and report on the visit of Margot Pampel from Australia on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Jenaplanschule Jena.

Year 2017

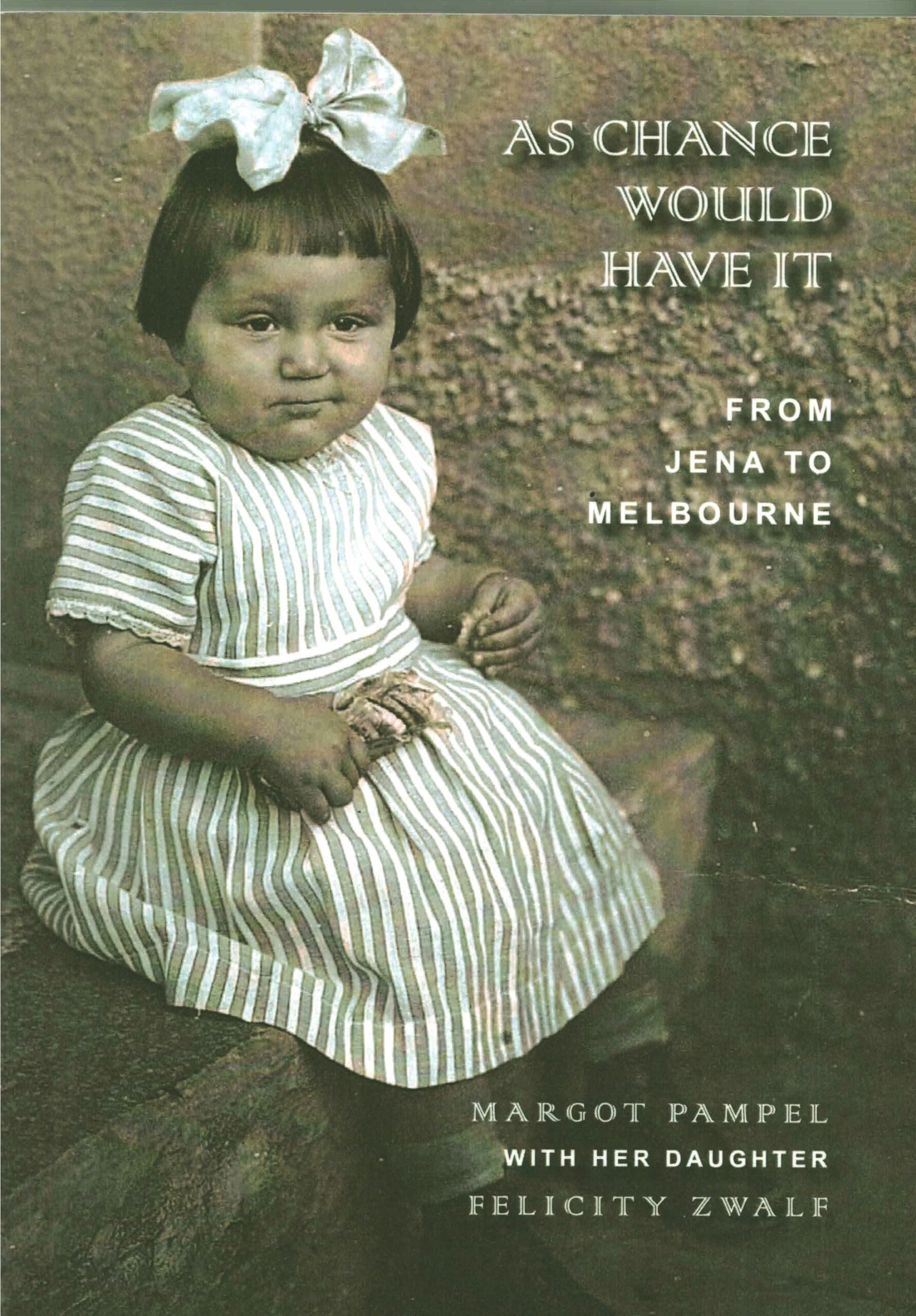

In 2017, the autobiography of Margot Pampel, née Reinhardt, was published by the “Lamm Jewish Library of Australia” with the title: AS CHANCE WOULD HAVE IT. FROM JENA TO MELBOURNE (Pampel, & Zwalf 2017). Here she tells in detail about her school days with Petersen and the subsequent ordeal; her mother, Gitta Reinhardt, experienced the fate of “Auschwitz”. She herself fled from Nazi-Jena and tried to hide.

Figure 16: Cover and title page of Margot Pampel’s book published in 2017, editorially supported by her daughter, Felicity Zwalf.

Year 2018

In 2018 the Springer Publishing House published the volume edited by Heiner Barz “Handbuch Bildungsreform und Reformpädagogik”. Among the articles that deal with well-known representatives of international reform education, one contribution is dedicated to Peter Petersen and the Jenaplan, with reference to the current state of discussion and research (see Retter, 2018).

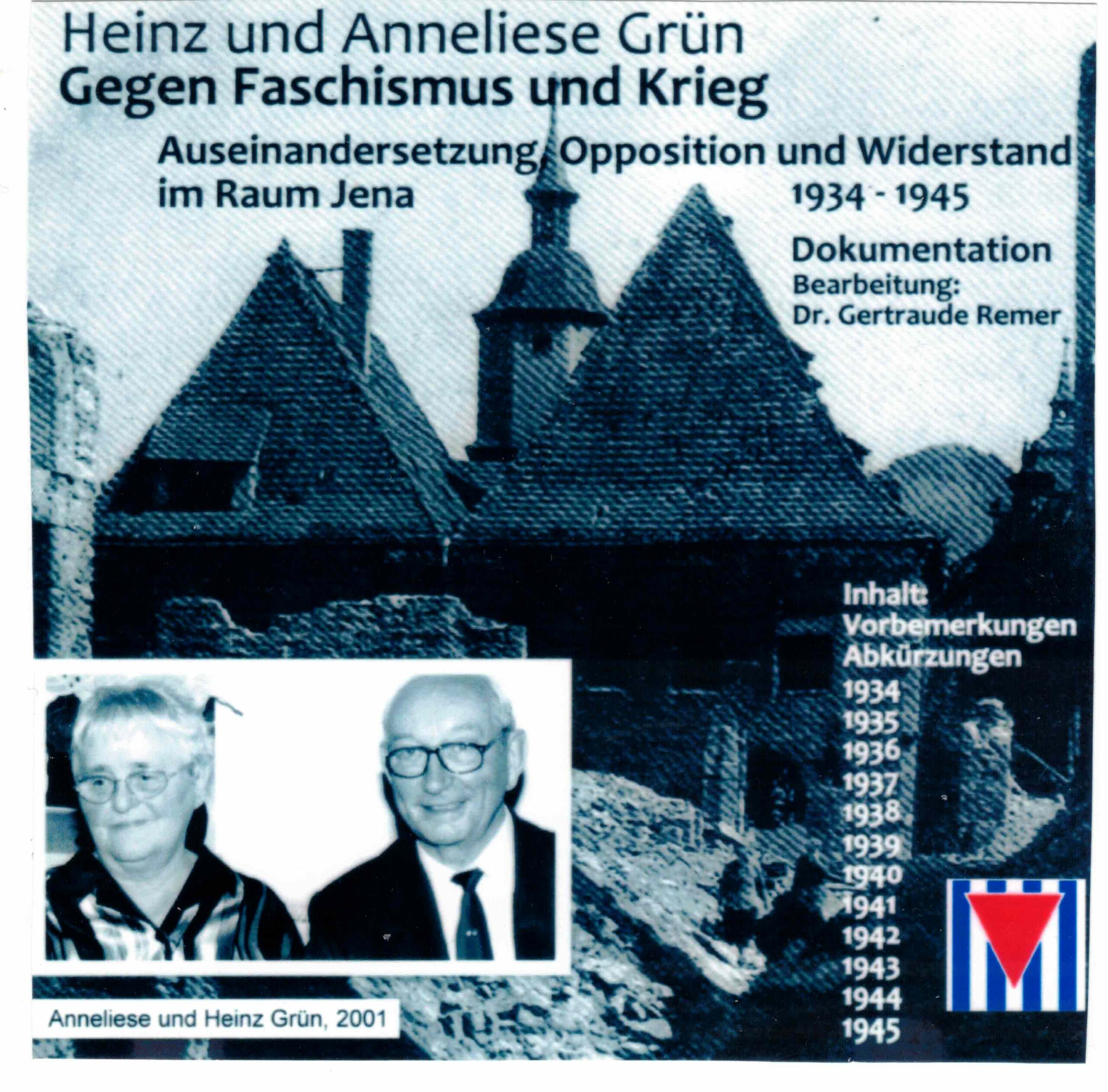

On September 10, 2018, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Thuringia presented a documentation from the scientific estate of Heinz Grün at the RLS office in Jena: “Opposition and Resistance in the Jena Area 1934-1945” (edited by Dr. Gertraude Remer). The material collected in earlier decades by the two researchers, Anneliese and Heinz Grün, could only now be published. The documentation which is now accessible in the Jena City Archive, is relevant for the Petersen research (see Grün, & Grün, 2018).

Figure 17: ISO-Image of the CD: Grün’s Documentation Against Fascism and War. “Conflict, Opposition and Resistance in the Jena Area 1934-1945.”

In the years before, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation kindly gave me the opportunity to use the unprocessed scientific estate of Heinz Grün, stored in various boxes at the RLS office in Jena, for my own research work. Also Michael Grün, Bad Kleinen, helped with supplementary material. Heinz Grün’s main documentation, on “Citizens of Jena and the surrounding area in resistance against the Nazi regime 1933 – 1945” (Grün, 2005) is now also available for all interested parties. I was lucky that my suggestion to put this work online was realized by the University Library of Jena.ii

Year 2019

In issue 1/2019 of the IDE-Online Journal the paper “How William H. Kilpatrick’s Project Method Came to Germany: “Progressive Education’ Against the Background of American-German Relations Before and After 1933” was published in International Dialogues: Past and Present: IDE-Online Journal, 6 (2019) no.1, pp. 88-124.

Figure 18: Front page of the essay by Hein Retter (2019), URL: IDE-2019-1-full.pdf, pp. 88-124.

The research report (including an evaluation of Kilpatrick’s correspondence and diary) on the background of German-American relations before and after 1933, shows how it came about that Petersen was able to publish the book “Der Projekt-Plan” in 1935. The volume contains essays (translated into German) by the two leading American representatives of progressive, democratic education, John Dewey and his student William H Kilpatrick. One should see, however,

(1) that Dewey and Kilpatrick completely ignored the problem of racism in the USA, the discrimination of African Americans, (2) that at the same time, in 1935, Petersen surrendered himself, his philosophy of education and Jenaplan to the Nazi ideology even more than before. Petersen achieved the Jenaplan’s demonstrative connection to the NS mainly through his programmatic treatise “Die erziehungswissenschaftlichen Grundlagen des Jena-Planes im Lichte des Nationalsozialismus” (Petersen, 1935), as well as through the text written by Herbert Sailer: “Why do we see the Jena Plan as the starting point for the National Socialist peasant school?” (Sailer, 1935).

Herbert Sailer (1912-1945) was a Hitler Youth leader (most recently “Stammführer”), a member of the SA since May 1933 and a teacher at the University School from 1935 to 1939. He taught the upper group, Anneliese Rau, teacher of the lower group from 1937, was also a young Hitler supporter. She had been a member of the “Bund Deutscher Mädel” (BDM) since October 1, 1932, and a NSDAP and NSLB candidate since April 1937 (UAJ: stock D, No. 2320). The middle group was taught by Dr. Ilse Opitz. She represented Christian confession-oriented convictions (Retter, 1996b, p. 32). The same applied to the religion teacher of the University School, Gertrud Schäfer (1897-1987). She was an opponent of the Nazi rule and those Nazi theologians who called themselves Deutsche Christen (German Christians), followers of Hitler and claiming that Jesus was not a Jew but an Aryan (see the German Wikipedia entry “Gertrud Schäfer”).iii

One can agree with Robert Döpp when he stated that curricular topics of the University School, as far as they are tangible, are not sufficient to “prove the fundamental Nazification of the University School. They show, however, that it is an illusion to want to understand the school beyond the other school reality in the Nazi era” (Döpp 2003, p. 429); that it was part of the everyday life of the University School when Sailer gave speeches in uniform and Petersen’s assistant Döpp-Vorwald visited the University School in SA uniform did not distinguish it from the school operations of other schools in its public commitment to the Nazi state (Döpp, ibid.).

6. International Understanding, Jewish Children and the Racism of Petersen after 1933

The political upheaval of 1933 leads the researcher, who is concerned with the fate of those families of the Petersen School in Jena who were politically left-wing or were counted among the “democrats” (i.e. the political centre), very quickly to the question: What did Petersen do with children whose fathers and/or mothers, for political, racial or other reasons (such as physical or mental handicaps), were fought against by the Nazis from 1933 onwards, so to speak as vermin? They absolutely contradicted Hitler’s idea of the German people as a racially “blood pure” Nazi community and partly the fathers fought actively in the resistance against the Nazis. Their existence was threatened by state measures as well as by arbitrary acts of violence during the Nazi dictatorship, which meant increasing humiliation, disenfranchisement, and finally systematic mass murder for those undesirable in the Nazi community.

Opponents of the volume “Jena University School” (Retter, 2010) argued: Here a danger for partly Jewish families had been constructed by the author of this book, which did not exist at all (Dokumente, 2011, p. 133). The argument was put forward: The “Jüdische Mischlinge” (Jewish race-mixed individuals) in Petersen’s school were in any case subject to compulsory schooling, they were in no danger of being excluded from it by law, neither at Petersen’s nor at any other public school in the 1930s, regardless of the question of the separation of Jewish and non-Jewish pupils in the course of the racial legislation from autumn 1935 onwards.iv

Unfortunately, the critics failed to recognize that Jewish “mixed race” individuals were exposed to dangers and even the feeling to have lost their own identity, due to Nazi law and the high degree of social isolation. This led to a life “In the Shadow of the Holocaust” (Tent, 2007).

This shows the school fate of Margot Pampel, however, said something quite different: she had to leave the secondary schoolv after the school management discovered her Jewish origin, which her mother had concealed (in accordance with Petersen’s advice), months before the introduction of the racial laws and the decrees restricting the conditions of existence of Jewish “Mischlinge”. As the school regulations of the University School of 1930 made clear under point 10 (Petersen, 1930, p. 204), those parents who “did not agree with the school spirit” were friendly asked to send their children “to another school”. In the end, Petersen alone decided; no state education authority could dispute his decision.

This also applied to partly Jewish families, which represent a larger group in Petersen’s parental and student body. They shared the fate of public stigmatization in the Nazi state, but were put in a state of constant, increasing fear not so much by laws as by locally arbitrary measures: Fear of discovery, of the Gestapo, of denunciation, of humiliation, of exploitation, of marginalization, of the violence of Nazi thugs: traumatic experiences of loss of identity that they retained for life (Tent, 2007; Gensch, & Grabowsky, 2010). If one parent was Jewish, the authorities were able to withdraw custody of the child from the parents, since education in the spirit of National Socialism was not guaranteed (Retter, 2010, pp. 172 ff.); for the current state of research on the topic of NS race legislation, see Brechtken et al. (2017).

“Mischlinge” (race-mixed persons) remained a problem for the Nazis from the very beginning, especially since Hitler, together with the party leadership and the SS, wanted to put them on an equal footing with the “full Jews” and exterminate them, while the ministerial bureaucracy strove to grant them a place in the Nazi national community as subhumans under degrading conditions until they would become extinct through social isolation. Schwan (in Dokumente, 2011, p. 120f.) took up the topic, but only quoted Beate Meyer’s dissertation (1999) from the more recent thematically relevant literature. His presentation was not oriented on the documented bad everyday life of the “half-Jews”, but emphasized their “special rights” that ministry officials intended to grant to the “mixed race” indivuals. But such alleged rights were more declarations of intent than reality; Gestapo and SS had no problem ignoring ministerial decrees when necessary. The practice of humiliation and exclusion from society was determined by the arbitrariness of local decision-makers and was practised in very different ways. This should not be forgotten: Not only Jews, but also “half-Jews” were tortured and murdered by the Nazis, already with the pogrom night in 1938 Reinhard Schramm (2001) used the example of his own family to show the extent to which even half-Jews were subjected to torture and murder under the Nazi dictatorship. A family in which the father died before 1933 and the Jewish widow raised the children alone was considered a Jewish family by the Nazis (ibid., p. 20).

While the Nazis tried to separate those groups of people they considered enemies of the people, Petersen’s pedagogical concept consisted in accepting all children – with parents of all social classes, world views, including parents with a physically and mentally handicapped child). Anyone who suspects the concept of “international understanding” behind this, which Petersen (1926) saw as the basis of a “New European educational movement”, will perceive that racism as a slap in the face, which Petersen developed after 1933. In Jena one remembered that in 1929 Petersen, through the circle of friends of the University School, had invited to a lecture by Prof. Dr. Albert Pinkewitsch, from the Second State University in Moscow, on “The Russian Elementary School” (Volksschule). It was known in Jena that Petersen had good relations with colleagues of the Soviet Union. This was the case in Schramm´s family, but the situation in the case of Margot Pampel was very similar: Her father, a communist, died after an accident in 1930.

Figure 19: Announcement of a lecture by Prof. Dr. Albert Pinkewitsch, Moscow, January 29, 1929,

“The New Russian Primary School”, in the assembly hall of the University School, Jena. Source: UAJ, stock S, I, No. 315, p. 125.

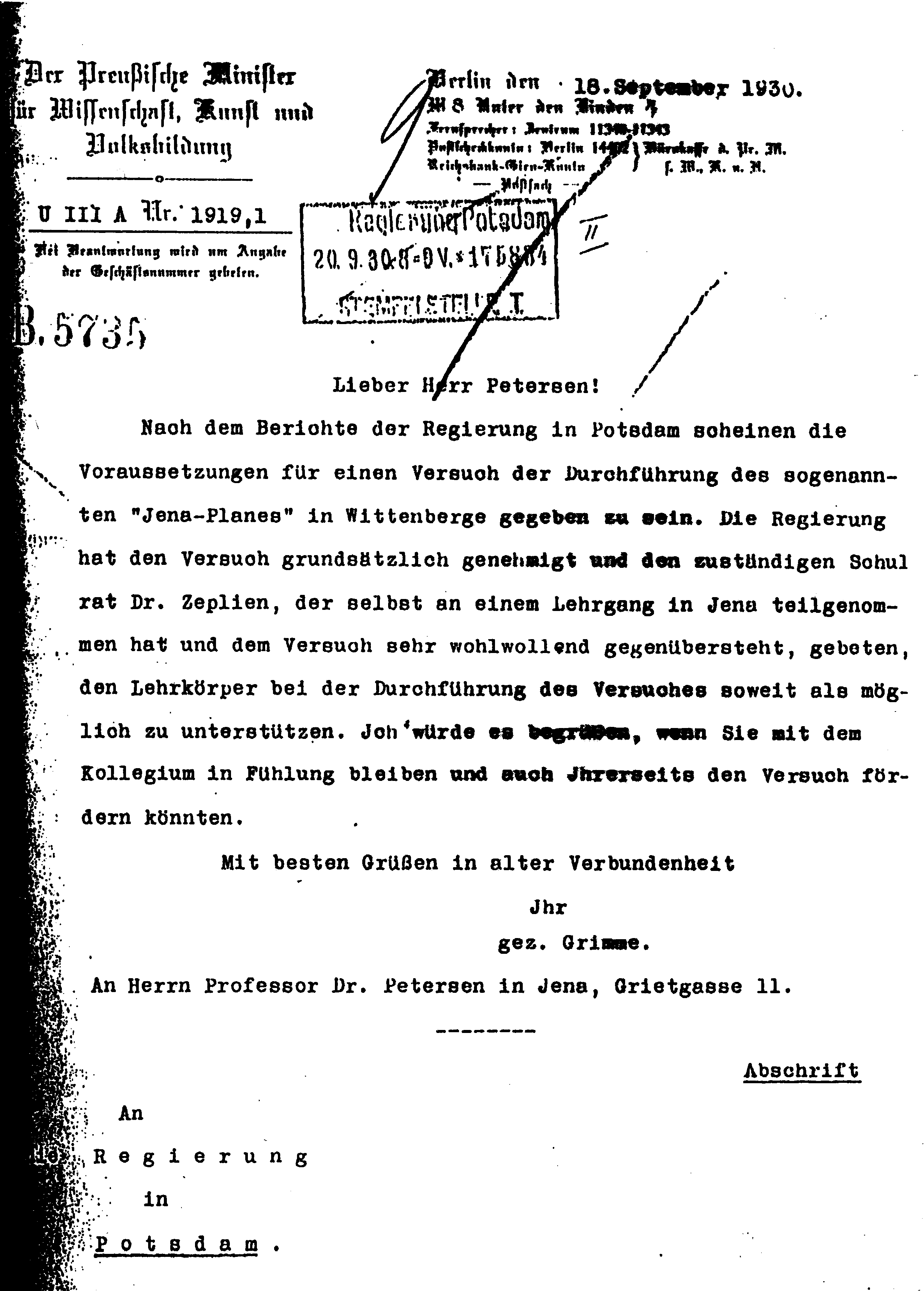

Already one year later the Nazis ruled in Thuringia, with the Baum/Frick cabinet. The year 1930 was also a climax of Petersen’s successes under the conditions of the first German democracy, the Weimar Republic. Not in Thuringia, where the Jenaplan had no followers outside of Jena, but in socialist-ruled Prussia, Petersen met with sustained interest in the Jenaplan among elementary school teachers on the political left. The Prussian Minister of Education, Adolf Grimme (SPD), approved the first Jenaplan experimental school by letter dated September 18, 1930: The text of the letter from Minister Grimme to Petersen read:

My dear Mr. Petersen! According to the reports of the government in Potsdam, the conditions for an attempt to implement the so-called “Jenaplan” in Wittenberge seem to have been met. The government has approved the experiment in principle and has ordered the responsible school councilor, Dr. Zeplin, who has himself taken part in a course in Jena and is very sympathetic to the experiment, to support the teaching staff in carrying out the experiment as far as possible. I would appreciate it if you could keep in touch with the teaching staff and also support the experiment on your part.

With best regards in old solidarity, Yours sincerely, gez. Grimme.

Figure 20: Letter from the Prussian Minister of Education, Adolf Grimme, dated September 18, 1930: Approval of the Jenaplan organisation of an elementaty school, in the town of Wittenberge.

With the coup d’état of the Reich Chancellor von Papen in the so-called “Prussian Strike” on July 20, 1932, the Prussian state government and thus also Minister of Education, Grimme, was deposed. From then on, the Social Democrat no longer belonged to Petersen’s political network. After Hitler came to power at the end of January 1933, Grimme was no longer interesting for Petersen.

The old Nazi Theodor Scheffer and the Nazi pedagogue Ernst Krieck with both his disciples Hördt and Kade were a springboard for Petersen’s move into Nazi circles (Retter, 2007, p. 295ff.). Before 1933, he was considered an internationally recognized reform pedagogue of liberal educational principles in Jena, who had gained respect in the Weimar democracy with his commitment to tolerance, humane attitudes and international understanding. Petersen’s idea of community had a cooperative, a socialist and a “völkisch” root, which he stressed, depending on the political requirements (Retter, 2007, p. 275ff.).

With his advocacy of the Hitler state in 1933, Petersen wanted to make his liberal concept of New Education forgotten in public space. At the same time, he tried to help his pedagogy to gain recognition, which in turn was only successful on a regional and short-term basis. At many points in this “contemporary” change of identity, ruptures arose which the Petersen research of the last decades has uncovered. The ambivalences of his change of system, which was carried out with flying colours, made Petersen a risk to the lasting memory of a community that honoured him at his place of work by naming a place, but could not know of this risk at the beginning of the political turnaround in 1991. The Petersen controversy 10 years ago helped to bring the problematic aspects of Petersen’s behaviour much more to the fore than was possible 30 years ago, immediately after the “Wende”.

Petersen’s active readiness to adapt to National Socialism is an old finding of Petersen research from the 1990s; but the full extent to which Petersen demonstratively presented Nazi ideological communities in his publications was first revealed by Ortmeyer. His study made Petersen – rightly so – guilty before the victims of the Holocaust and was suitable for questioning the moral substance of the Jenaplan.

In 1933, the following applied to the students of the Jena University School: Unless a normal transfer to a secondary school took place, all children continued to attend Petersen’s school. The fact that there were fathers from the left-wing milieu in Petersen’s school community who joined the resistance is attested to by documents on Jena’s local history in the Third Reich. The fact that well-known socialists, such as Paul (v.) Hermberg (SPD) or the high KPD functionary Alfred Noll (Weber, 2004, p. 539f.) emigrated to far-flung countries is shown in the specialist literature. But that they had their children in the University School and that these children continued to attend Petersen’s school from 1933 onwards can only be found out from the parent/pupil lists of the university archive Jena – for the first time in the volume “Retter, 2010”. Ortmeyer interpreted the subject of the book in his own way with the statement:

“Equating the discrimination of resistance fighters who were harassed and threatened [with] the fate of Jewish children and the children of Sinti/Roma in the gas chambers is already a step to relativize and put aside the uniqueness of the history of the state-organized and industrial genocide” (Ortmeyer, in Documents, 2011, p. 41).

It was somewhat embarrassing when recognized victims of National Socialism and their children were instructed in their painful fate by the spokesmen of the Jena Petersen discussion: You were only harassed, but you were not among those who were sent to the gas chambers. So everything is not so bad for you!

Apparently Ortmeyer tried to play down left-wing opposition and resistance in Jena to the Nazi regime by referring to the Nazi genocide. If one follows such accusation of “putting aside the genocide” to Thuringian conditions, one can only be concerned how he dealt with the fate of Lydia and Magnus Poser, for example – in application of what he outlined in the sentence quoted above. Lydia Orban, married Poser, was arrested several times by the Nazis and spent “only” two years in prison. The arrest of Lydia and Magnus Poser on July 4, 1944 ended with the murder of Magnus Poser: While Lydia Poser was released from custody after two days, her husband attempted to escape from the Gestapo prison in Weimar. The chance of success was small. He accepted death in order not to have the names of his fellow combatants squeezed out of him by torture. Magnus Poser died from the bullet wounds of his guards on July 21, 1944 in the sick bay of Buchenwald concentration camp (Schilling, 2006, p. 340). But in terms of Ortmeyer’s normative commandment, the whole thing did not have the quality of the perfect mass murder. If one follows Ortmeyer’s offer of interpretation, the death of Magnus Poser is rather the regrettable consequence of the “chicanery” and “threat” of a resistance fighter, apparently of inferior importance for the culture of remembrance.

The same applies to the suffering of those persecuted by the NS and their families in the Petersen School. Heinz Grün had interviewed Rolf Schrade in 1980. The records from the scientific estate did not become accessible to the public until 2018.

From a conversation with Dr. Rolf Schrade

[Hugo Schrade refused to divorce his Jewish wife. Already in 1938 Zeiss employees had offered him that his wife and son should live in Switzerland at Zeiss’ expense. He did not accept the offer. On 15 October 1944 he was taken to the forced labor camp in Weißenfels, Halle. Prof. Ibrahim took Mrs. Schrade and her son to his children’s hospital in case of danger. The daughter of Ernst Abbe, Grete Unrein, was a friend of Schrades. She brought Rolf Schrade, who as a child had been abused and beaten up with ‘Judmann’, to his parents’ apartment. Before this beating Rolf Schrade was not aware that he was of Jewish descent.

On 31 January 1945 Rolf Schrade was with us at the Saal-Bahnhof when his mother was taken away with Jewish women, among others. The night before, [the Jewish doctor, Mrs.] Dr. [Klara] Griefhahn had committed suicide. It was a traumatic experience for him. He had an inkling of what the transport would mean. Although 40 years have passed, he is still afraid today.

Head of the transport to Theresienstadt concentration camp was a certain Waldemar Eissfeld. He was tried in 1952 by the jury court in Darmstadt for deprivation of liberty. Mrs. Schrade also testified at the trial. After the war, Mrs. Schrade and her son Probst visited Grübervi in Berlin. – H. G.]

See Pastor Schröter, Jena, minutes of a meeting with Dr. Rolf Schrade on April 25, 1988 in Jena, transcribed in the personnel file by H.G. Source: Grün & Grün 2018, year 1945.

To speak of “Jewish children” does not necessarily mean to follow the classification of the Nazi laws. The term is also used in today’s documentaries in a value-neutral way (as a collective term), while those affected experienced it as a malicious stigmatization under the Hitler regime: The characteristic as “Jewish”, which they had not emphasized before, now became an incriminating part of their self-image, even if they were “only” half or quarter Jewish, according to Nazi laws. Among those still living of that generation who fled from the Nazis at the time, even though they were not “fully Jewish”, the Jewish part of their own identity could – as a reaction to this oppressive experience – be particularly appreciated in the decades after the end of Nazi rule (Cotton, 2008, p. 16, p. 104f.).

Jena did not have very many Jewish inhabitants during the Weimar Republic compared to other cities. In 1925 there were 277, but by 1933 the number had already shrunk to 111, with a population of just under 60,000 (Arbeitskreis Judentum 1998, p. 50f.). In the bourgeois intellectual milieu, which includes university professors and the leading staff of Carl-Zeiss, it was not unusual, however, for a number of married couples to fall under the Nazi classification of a “mixed marriage”.

During the Weimar Republic, the university town of Jena had neither its own Jewish cemetery or synagogue nor a rabbi; for worship, religious instruction, pastoral care and highlights of Jewish life, the Jews of Jena were cared for by rabbis from outside the town. Thus it was not to be expected that the University School would be attended by a larger number of Jewish students, especially since Petersen clearly developed its profile from 1930 onwards in the direction of a Protestant denominational school. In contrast, the proportion of socialist-oriented families in the industrial city of Jena was quite significant. This plays a role in the origin of the parenthood of the University School. This fact is also fundamental to the much higher proportion of socialist families in the University School compared with families of Jewish origin.

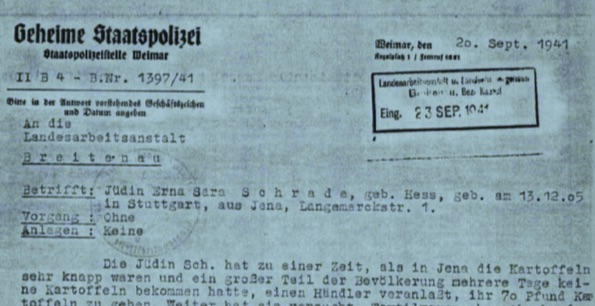

Figure 21: Deportation of Erna Schrade by the Gestapo to the Breitenau labor camp near Kassel, after she had been denounced by her landlord (from the “Files for Erna Sarah Schrade,” Schutzhäftling, Breitenau labor camp; Access: September 26, 1941; Source: ITS).

Gisela Horn provided more detailed information on Erna Schrade’s situation at the time: “The mere purchase of a large quantity of potatoes, which she had also purchased for another suffering family, was enough to send her to a labour camp in Breitenau near Kassel for three weeks […] At the same time, she herself was concerned to support other persecuted persons, so she contacted Propst Grüber and the “Relief Centre for Non-Aryan Christians” run by him (G.H. in: Jüdische Lebenswege, 2015, p. 453f.).

In a curriculum vitae of 25 March 1947 Erna Schrade wrote:

“Since I am of Jewish descent, I and my relatives were persecuted during the Nazi regime under the Nuremberg Laws. During the past 12 years, my husband has only experienced difficulties in his professional life. The then NSDAP district leader Müller used every opportunity to insult and oppress us. On the basis of a denunciation, I was arrested by the Gestapo in 1941 and from September to October I was taken to the Breitenau labor camp, where I had to do hard, physical labor. My relatives did not know where and for how long I was arrested. As a result of racial persecution I was taken to the camp at Theresienstadt in January 1945 […] My brother Siegfried was murdered in Maidanek near Lublin.” (Erna Schrade, CV 1947; source: ITS)

In fact, no one in Jena doubted that in the case of Erna and Hugo Schrade the experience of their son Rolf was worth being perceived and not suppressed by the culture of memory (cf. Jüdische Lebenswege, 2015, p. 452ff; Jena-Lexikon 2018, p. 560f.).

It was Margot Pampel who referred me to Elisabeth Scheinok and Ulrich Dannemann. She had found both of them at the Petersenschule after she had been enrolled there. Both were “Jewish children”, had Jewish parents, but were not victims of the Nazi regime during their school days at Petersen: Elisabeth experienced on April 1, 1933, how her parents’ shop was occupied by SA troops. Among the Jewish shops that were excluded from the delivery of goods in June 1933 was Aron Scheinok (Grün, 2003, p. 330). The Scheinok family was arrested in late October 1938 in the so-called Poland Action, which was followed by the deportation and presumed murder of the entire family (Jüdische Lebenswege, 2015, p. 437f.). Ulrich Dannemann moved with his parents to Cologne, went into exile with his father to Brazil in 1935 and returned to Germany after the war. In 1951 his former classmate Margot visited him (Pampel & Zwalf 2017, p. 156ff.).

Holocaust remembrance in the GDR: The GDR had an initially ambivalent and, from the 1950s on, a rather oppressive political attitude towards Holocaust remembrance. The GDR leadership honoured the victims of fascism. What was it like in Thuringia, in the territory of the East German state? Jews who had been able to escape the Holocaust and returned to Jena after the fall of the Hitler Empire saw no chance of continuing their former economic existence; they left the city for West Germany (Arbeitskreis Judentum, 1998, p. 184ff.) In the course of the change of political system from 1990 onwards, Jena – like other cities in the former GDR that now belong to the Federal Republic of Germany – had to undergo an extensive programme of renaming street names. In East Germany, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was founded on 7 October 1949 under the leadership of the SED, which created its own communist culture of remembrance: by naming streets after the founding fathers of the ruling state doctrine, the victims and living models. After 1990, however, street names that recalled the past decades of the socialist state were a nuisance to the citizens.

At the same time, there was a new interest in awakening the memory of the Holocaust and of the historical Judaism of Jena and keeping it alive in remembrance. After the political turnaround, Jena’s culture of remembrance had attempted, in an often difficult search for traces, to wrest all Jewish families who had suffered under National Socialism from the widespread ignorance of the local public. The aim was to remember and honour them. The “Jena Arbeitskreis Judentum”, founded in 1997, did not forget in its work those who managed to evade the Nazis by fleeing and emigrating, nor did it exclude those who, because the Nazi legislation “only” classified them as half-Jews or quarter-Jews (“first or second degree race-mixed”), also suffered injustice and began their deportation for murder not only in the last weeks of the fall of Hitler’s Germany, but already after the November pogrom in 1938. A first result of the historical search for the victims of the Nazi dictatorship in Jena was published in 1998 by the Jenaer Arbeitskreis Judentum.

7. Learning Processes – Insights about Petersen and the Actors Involved in the Petersen Discussion

In several large-scale studies on Petersen (Döpp, 2003; Retter, 2007), problematic activities during the Second World War were discussed in detail, such as Petersen’s lectures in the Buchenwald concentration camp to deported Norwegian students of the University of Oslo, the lectures in elite institutions of the Hitler Youth – as well as several Nazi ideological texts. From 1941 to 1944, advanced training courses for heads of the Reich Labour Service of the Women’s Youth (RADwJ) were held at the University of Jena under Petersen’s organizational direction (detailed: Retter, 2007, p. 429ff.). In May 1945 the Nazi regime was finally defeated.